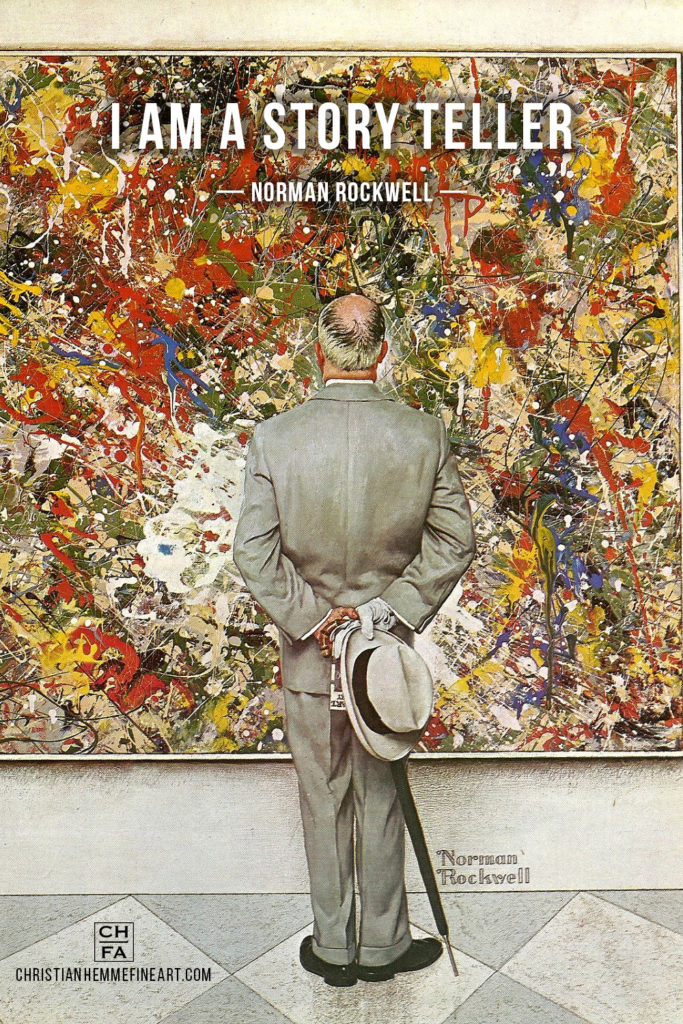

Essence Versus Exactness | Artist Quotes | Norman Rockwell

“I am a story teller.”

—Norman Rockwell

Learn more about Norman Rockwell, who lived from 1894 to 1978.

This iconic American illustrator captured the soul of a generation of Americans.

Essence Versus Exactness

I recently wrote a letter in which I attempted to describe my painting style. “I love trying to achieve accuracy in the form, texture, and color of my subjects while still having a more bold, loose, and textural painting style. Somewhere in-between impressionism and photorealism, let’s say.” The concepts of careful painting, bold painting, abstract painting, and postmodern techniques have been in my mind a lot lately.

In fact, this tension amongst techniques has always held a particular fascination for me. After all, the process of a painter conveying ideas through a visual medium relies rather heavily on how he or she applies the paint! It seems a lot of the tension arises from this concept of “essence versus exactness.” How do we as artists say what we want to say without “overworking” the painting? When do we call a painting “finished?” (Contemporary master Richard Schmid said: “It often takes two to do a good painting — one to paint it, and another to rap the painter smartly with a hammer before he or she can ruin it.”) Well based on the art that’s been created within the last century or so, I’d say other people have wrestled with this idea also!

A Brief History of Art

From what I’ve studied, artists for millennia depicted mainly religious and mythological scenes, or were commissioned for portraiture. These artists usually created stylized images which, although certainly conveying their message, didn’t particularly attempt to look realistic. In early Western culture, iconography represented one of the main expressions of painting. The purpose of iconography was to translate Scripture and theology into a non-literary form. (Since most of the population was illiterate, this sounds like a good idea to me!) However, starting with the likes of Giotto, artists began to desire to depict their subjects with more realism. Why not make paintings that both convey the message and have visual accuracy?

The Baroque artists took this idea to the next level by exploring light and shadow more in depth. Chiaroscuro became the norm, and paintings took on an ever-increasing degree of reality. As the centuries rolled on, artists kept refining their paint application methods, until a standard “traditional method” became established.

The premier art show in Europe, the Salon de Paris, favored artists who worked in this academic style. Salon painters apparently attempted both to make their paintings as exact as possible and, according to some sources, also smooth as glass! It’s difficult in our day to think of how striking “photorealism,” or something very near to it, must have been before the introduction of photography. Imagine the level of skill these artists possessed to create paintings that, even today, we might consider photo-realistic! The keen visual observation, patience, and attention to detail are all extraordinary! The paintings of William-Adolphe Bouguereau represent this era particularly well.

But then a genre of painters came on the scene that questioned the increasingly formulaic processes and intricate detail. To these individuals, academy formulas produced paintings that lacked expression and appeared lifeless despite all the detail.

These painters, dubbed Impressionists, desired to capture the essence of a scene, and they frequently sacrificed detail to do so. Often working from life and using direct-application and “broken color” techniques, they focused on the immediate impressions and colors of a scene. Nowadays when we hear the term Impressionism, we might think primarily of the French impressionists: Monet being the foremost. But the impressionism movement goes far beyond that master’s iconic works. The illustrious American John Singer Sargent and Swedish genius Anders Zorn are just two examples from outside of the school of “French Impressionism.” These two and other impressionist painters utilized a full range of lights and darks, and also weren’t afraid to use more neutral colors.

A few decades and a couple world wars later, even the idea of creating a recognizable image came into question. Many traditional ideas and paradigms were challenged. What had been considered obvious or true came into doubt. In art, painters began exploring non-representational works. These paintings generally still attempted to convey a feeling, emotion, or message, but the subject didn’t have to appear real—or even be recognizable. In this “modern” art, a viewer could comprehend the message immediately, intuitively, without the bother of discerning actual things.

And finally, we’ve now moved into “post-modern” art, which tries to defy everything else, even modernism. Random, bizarre, macabre, and chaos define this style. Artists in this genre simply attempt to be unique. The work itself and how the paint is applied, much less the emotion or mood to be conveyed, became of little importance. Originality and the defying of all accepted norms take center stage in this genre.

(An example of the mindset of this sort of artist comes readily to mind. I recently watched a short, interesting interview with the creator of the font Comic Sans. His perspective of what makes “good art” aligns with my description above. “If you didn’t notice [the art], I considered that was bad, and if you did notice, it was good, because at least they made you stop and look. It either shocked you, or you really liked it. But if you didn’t even notice, and you just walked through, it was a disaster.” Full interview here.)

Where the Balanced Things Are

As in all things, I think art and the method of its creation require proper balance. In our modern and post-modern times, I believe a lot of “art” is a total sham. The people who create and sell this sort of rubbish simply want to make money or garner fame through shock value and weirdness. The artist’s skill, and even genuine originality, have little to do with it. But please don’t construe my statement of needing balance as constrictive! Within the balance, there exists an almost infinite variety to be explored.

For years in my own work, I strove mainly for exactness, in the Academic tradition. (This painting shows a good examples of that period.) A perfectionist at heart, I still fight the impulse to refine paintings to a near-photographic quality. Exactness is such a huge part of who I am! I still enjoy hearing the comment “It looks like a photo!” as people view my work in person or online.

(An interesting side-note: a lot of artists become rather offended when someone says their painting “looks like a photograph.” Although they realize people mean it as a complement, the phrase has been overused to the point of being grating. Especially when an artist has carefully utilized painterly brushwork and bold textures, it can come across as rather a slap in the face. However, I’ve come to really appreciate when people make this sort of comment about my work. Because what people really mean by “It looks like a photograph!” is that the painting looks real. And if the painting looks real, then I’ve achieved to some extent that essence I desired. Nowadays whenever I see an artist becoming bent out of shape on hearing this sort of thing, I try to present this point of view. It usually goes over pretty well.)

But like the impressionists, I began to realize that my paintings lacked something. Although I had been describing myself as a “visual storyteller,” I noticed that my work frequently lost its message in the details.

So I began to seek to “loosen up”; trying to regain that focus on essence. I began working with bigger brushes and in a bigger way. Not as much blending together. Letting textures and colors scatter about to create nuances otherwise impossible. Studying bold painting styles exemplified by the Russian school, as well as artists like the aforementioned John Singer Sargent. I began painting from life more, and even started setting timers while painting in the studio so that I would be forced to keep a spontaneous feel. I feel that my work has benefited greatly from this “loosening up”; friends and loved ones have confirmed that notion. My goal remains the same, namely, to convey my message to my viewer. However, my technique has changed over time in order to better achieve that goal. (A more recent painting.)

John Carlson stated it well in his book Carlson’s Guide to Landscape Painting: “How shall we approach our task of rendering these aesthetic experiences upon canvas so that our brother man may feel them with us?”

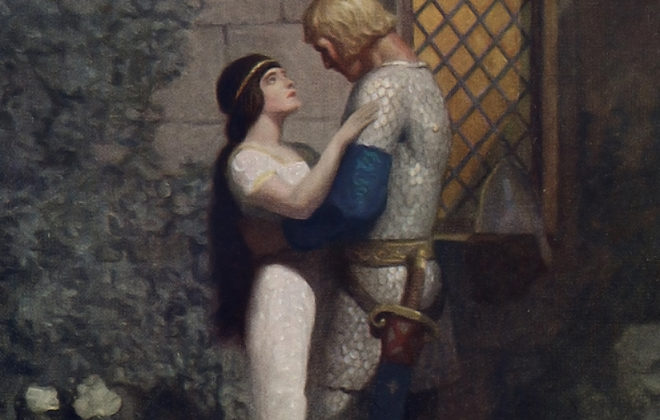

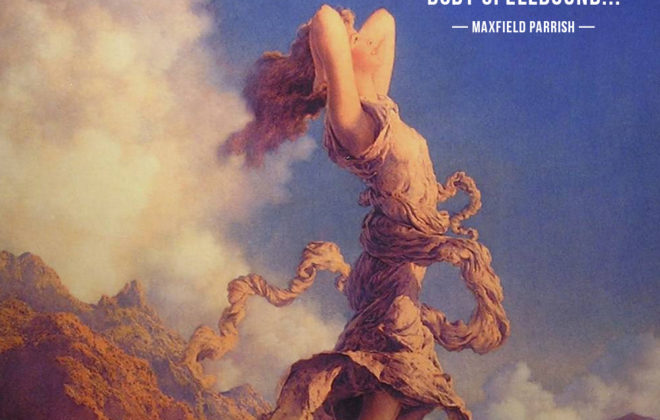

Here are a few contemporary artists who I believe strike a good balance between essence and exactness: Joshua Clare, Mian Situ, Brian Jekel, and Richard Schmid—just to name a few. The illustrators from the “Golden Age of Illustration” also exemplify this ability: Dean Cornwell, N.C. Wyeth, Maxfield Parrish, and Alphonse Mucha.

Question: Which do you prefer to predominate in a work of art: “Essence” or “Exactness”? If you’re an artist, which do you naturally lean toward in your paintings? Have you found a way to strike a balance that you would like to share? Let us all know in the comment section below!