First, A Bit of Context...

INTRODUCTION

Propositions, Protestants, and My Past

Background and Rationale

Hypocrites. How often has that accusation been pronounced in contemporary culture against individuals who claim to be followers of Jesus Christ? More importantly, how often is the statement accurate? From observation within my own spheres of life, I can say without reservation—though certainly with a fair amount of trepidation—the description has been justly deserved quite frequently, through actions and words both ignorant and intentional. Worst of all, I am also acutely aware of the degree to which the epithet could have been correctly applied to me. By God’s grace, I believe that in my own life, instances of “claiming to have moral standards or beliefs to which one's own behavior does not conform” (“hypocrisy”) have been greatly reduced as the years roll by; however, I have not yet “obtained this or am already perfect” (The Holy Bible, Phil. 3.12). Many of those times and places where I have blatantly disgraced the Triune God still smolder shamefully in my memory. This sort of defiance to the Person and eternal laws of God, whether in my life or the lives of others, often leaves in its wake human suffering the sum of which would destroy anyone who could fully grasp it. The theological term for a state of affairs where such consequences become eternal, intractable reality is hell. Some people already experience a small, horrendous sampling of this torment in their draught of earthly life—but all who engage in rebellious opposition to the character and decrees of God effectively actualize currents from hell’s ocean of misery.

I have described myself to many people as “the least artistic artist that I know personally.” (However, I also have an exceptionally poor memory, so best take that self-assessment with a large grain of salt.) When given leisure time to pursue personal interests and activities, one would rarely find me with pencil in hand sketching compositional ideas or watching Disney+ videos about Pixar’s creative processes (although these events certainly do occur). As that opening paragraph likely communicates, my mind turns towards existential questions and contemplation of ultimate truth (also world football, what we in the U.S. call soccer, but that point is entirely tangential to this thesis. Viva Barça.) In short, and in retrospect, I probably should have studied philosophy and theology as an undergraduate…except that for many years before college, and continuing through the present day, a still, small, unceasing Voice has kept a passion alive in my whole being. And that passion is visual art.

(Fig. 1 | St. Peter Paul, oil painting by the author)

I wanted to be a professional artist from an early age; however, the life-path down which God led me was far more winding and unpredictable than I could have imagined. After college, I spent nearly a decade as a rather frustrated “independent fine art professional” (as my tax paperwork labeled me), continually struggling to find viable ways to impart a deeper significance within my studio work while remaining solvent. After marriage, and with the encouragement and help of a loving Wife, I felt God’s call to return to academia and pursue a master’s degree. It was within this postgraduate context that I found direction and fulfilment which had proven so elusive beforehand, as 10 years of practical working experience combined with scholarship in both art and theology-philosophy (hyphenated, as the two are inseparable). I began to have a clearer vision of how God, in His infinite and patient lovingkindness, had been uniquely crafting me for His purposes (if a certain verse from Ephesians 2 springs to mind here, good: it ought to). The confluence of these purviews also began to pose an increasing number of questions that I deemed to be quite important: one of which became the focus of this thesis. But to introduce that line of inquiry, and to (finally) tie in my grave and disconcerting discussion of hypocrisy and hell, another short narrative is in order.

(Fig. 2 | Christian Hemme Fine Art Logo)

"It was within this postgraduate context that I found direction and fulfilment which had proven so elusive beforehand, as 10 years of practical working experience combined with scholarship in both art and theology-philosophy (hyphenated, as the two are inseparable)."

During my MFA studies, I undertook a rather unexpected practicum at a stained-glass studio in Lynchburg, Virginia. (Unexpected, considering my portfolio at the time consisted primarily of nautical-themed oil paintings and literally no stained-glass work—I was introduced to the vitreous medium during my second year of graduate school, in a class studying the Arts and Crafts movement). The studio, Lynchburg Stained Glass, creates windows in a variety of styles and sizes almost exclusively for houses of worship—this ancient artform has long been closely associated with Christianity, and the very mention of stained glass might conjure mental images of dark cathedrals, smoking censors, and Gregorian chant sung by hooded monks. I quickly fell in love with the medium.

It just so happened that this Arts and Crafts class and subsequent internship experience followed closely on the heels of a multi-year, personal, in-depth exploration of various philosophical concepts centered around the Christian faith. My journey was facilitated primarily by the podcast of philosopher and Christian apologist William Lane Craig, although recorded lectures by former Asbury University Professor of Philosophy Christopher Bounds; daily readings of John Wesley and John Chrysostom; and repeatedly streamed Sunday morning sermons from Methodist Minister Ralph Sigler also played central roles. During this period, the relevance of orthodox Christian doctrine regarding foundational existential questions became increasingly evident to me. Historical, traditional Christianity stood in utter superiority to all other worldviews and truth claims in its ability to provide coherent, reasonable answers to those inescapable inquiries that burn in so many minds and hearts—those unknowns that frequently consternate, and even consume, the human soul.

(Fig. 3 | A selection of glass samples at Lynchburg Stained Glass)

As I continued to plumb the depths of Christianity’s tenets, progressively understanding their absolute essentiality for the function, health, and happiness of humanity, I simultaneously began to see how the flouting of proper dogma—and the way of life incumbent in such statements—has horrifying ramifications. And it is at this point that two-facedness and hell’s gaping maw become manifest. The Bible explicitly lists a series of activities that excludes those who practice them from inheriting the Kingdom of God, such things as sexual immorality, drunkenness, and jealousy (Gal 5.19-21). The inescapable implication within these verses is that people who purposefully, continually engage in these behaviors attain unto hell…and the collection of evils that the Apostle Paul names are distressingly commonplace in the 21st-century United States. The atrocious, infuriating reality is that many of the same individuals who most ardently pursue what could be called “the fruits of the demonic” claim the moniker “Christian.” And again, that hypocritical individual has, many times, been me.

Such was my honest observation, and I was decidedly upset by it: the apparent lack of understanding, and subsequent scarcity of enactment (or downright disobedience), of crucial Christian principles by ostensible adherents must be unequivocally addressed. Therefore, when beginning to formulate a thesis as the culmination of my MFA studies, I quickly concentrated on this issue. The foundational question soon became apparent: how to facilitate the inculcation of Christian doctrine through my sphere of expertise, the visual arts? It seemed necessary to narrow the inquiry’s scope to a more manageable demographic, so I confined my investigation to that culture with which I am most familiar, namely, U.S. Protestants. During my previous forays into Church history and thought, I had come across an historical process for training new adherents to Christianity, called catechesis, which had left a favorable impression on my mind as a sound means for religious teaching today. Therefore, I decided to commence my scholarship considering a catechetical model as the framework in which to employ instructional imagery.

(Fig 4. | Byzantine mosaic in the Hagia Sophia of St. John Chrysostom, c. A.D. 1000 | https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/c/cf/Johnchrysostom.jpg?. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021 |

Photo by Ch.Andrew, Public Domain)

Purpose and Process

This thesis explores improving comprehension and retention of orthodox Protestant doctrine in the United States through integrating pictorial illustrations into the classic Christian pedagogical methodology of catechesis. Because of unceasing debates surrounding the numerous, nuanced theological stances among different orthodox Christian sects, this study will focus on those elements of the faith that would be, as nearly as possible, universally accepted as comprising “‘mere’ Christianity” (to use C.S. Lewis’ phraseology, appropriated in turn from Richard Baxter) (Lewis vii; Keeble 27-31).

To evaluate an efficacious solution, several concerns had to be resolved. First, it was necessary to determine that a problem did indeed exist. Are U.S. Protestants quite as misapprehensive as I perceived them to be? Survey results could reveal quantitative data on this front. Next, although I had a favorable opinion of catechesis, my holistic familiarity on the subject was limited. I was unsure of both its prevalence among Protestant churches, either historically or contemporarily, and whether there were already systems of catechizing which have incorporated pictures. A review of relevant scholarly literature was needed. Further, on a slightly more esoteric line (though no less essential considering my demographic), I wondered what potential barriers the consequences of Reformation iconoclasm posed to the assimilation of visual illustrations into 21st century doctrinal instruction. Again, academic research would probably shed light on this matter. Fourth, data and ideas gathered from the fields of science and education could clarify the mode and extent to which imagery increases learning outcomes. Last, a case study of artwork from the workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder, brief visual analysis of didactic Protestant images since the Reformation (excluding digital media), and a review of recent attempts at integrating pictures and text within catechesis would guide my own aesthetic approach. By analyzing, assessing, and synthesizing the solutions of Protestant artists both historical and modern, this new artwork would be strongly informed by, and placed firmly within, the tradition of its Protestant antecedents.

(Fig. 5 | Meunier, Jules-Alexis, The Catechism Lesson, 1890, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Besançon, Besançon, France | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Jules-Alexis_Muenier_-_La_Leçon_de_catéchisme.jpg.

Accessed 27 Feb. 2021 | Photo by Botaurus, Public Domain)

"This thesis explores improving comprehension and retention of orthodox Protestant doctrine in the United States through integrating pictorial illustrations into the classic Christian pedagogical methodology of catechesis."

Relevance and Significance

Although the alarming practical and spiritual repercussions of neglect or disregard for proper Christian dogma have been mentioned, the joyous, life-giving temporal and eternal results of its cherishing and enactment certainly merit stating as well. The theoretical bolstering of recognizing, grasping, and recalling doctrine, along with an accompanying increase in sustained implementation thereof, would certainly have several effects on U.S. Protestantism. First, heterodoxy—from simple error to outright heresy—could be more clearly and quickly addressed, plausibly resulting in an expansion of flourishing congregations of truly dedicated Believers. Second, during catechesis, initiates to Protestant Christianity would build relationships in the community of believers, an interconnectedness that Scripture commands (Prov. 27.17, 1 Cor. 12.12, Heb. 10.25). Comprehension and a continually deepening exploration of the faith’s tenets in the lives of converts would foster intellectual and spiritual growth throughout life, aiding resistance to stagnation and the retrogression that idleness inherently brings. Last, learning (from a Biblical perspective certainly) begins at home, and robust catechizing in the familial unit would strengthen those domestic relationships. Virtues such as compassion, humility, respect, and charity would be stimulated as family members grow in the knowledge, wisdom, and love of the character and Person of the Triune God.

(Fig. 6 | Pace, E.J., Descent of the Modernists, published 1922 |

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/1/10/Descent_of_the_Modernists%2C_E._J._Pace%2C_Christian_Cartoons%2C_1922.jpg. Accessed 15 Jan. 2021 | Image by Brian0918, Public Domain

Research, Revelations, and Resolutions

LITERATURE REVIEW & CASE STUDY

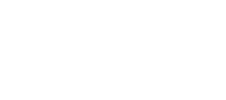

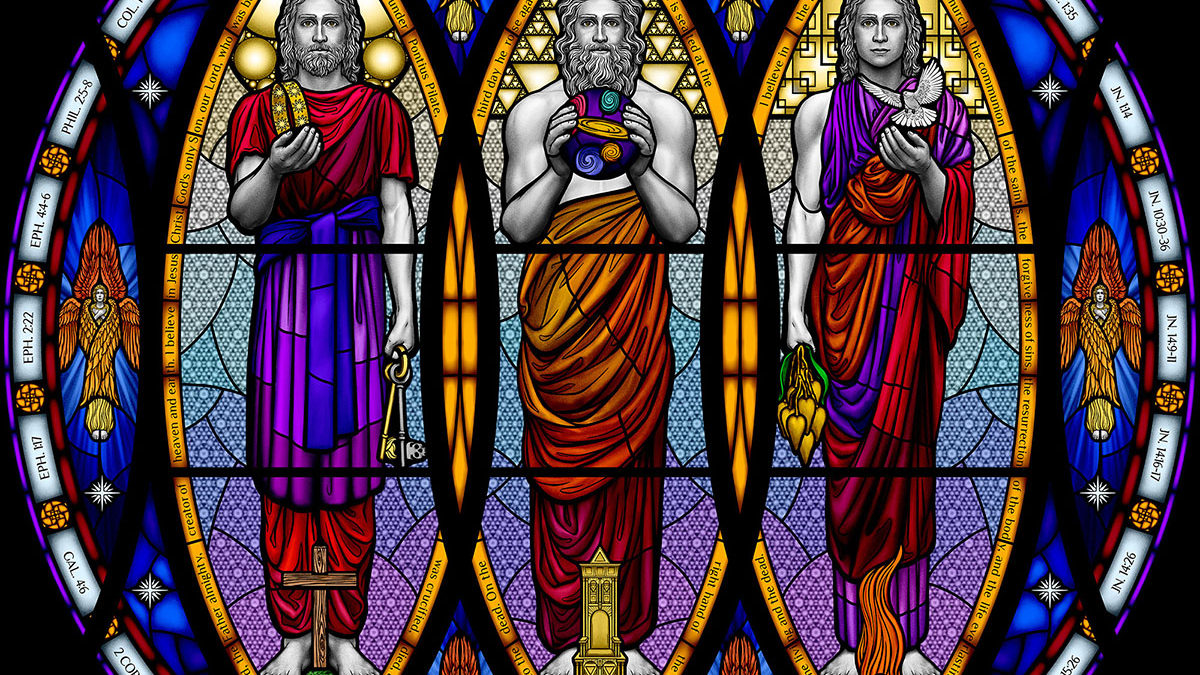

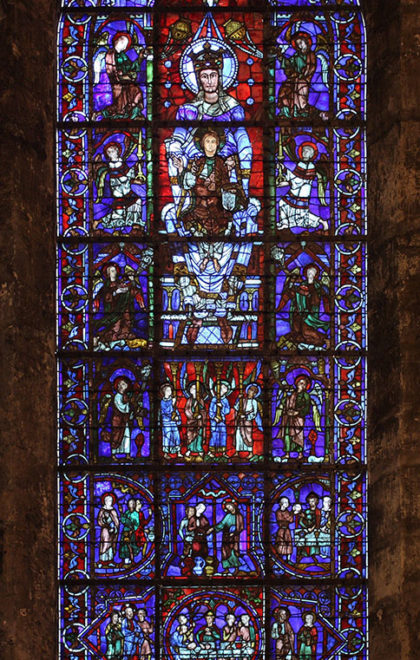

Fig. 7 | Genga, Girolamo, Saint Augustine Giving the Habit of His Order to Three Catechumens, 1516−1518, The Columbia Museum of Art, South Carolina | https://www.columbiamuseum.org/sites/default/files/styles/open_crop/public/2019-01/Screenshot%20%2827%29.png?itok=BsliE0VF. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021 | Photo by Colombia Museum of Art, Public Domain Fig. 8 |Notre-Dame de la Belle-Verrière, stained glass window, 1180, Chartres Cathedral | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chartres_Cathedral#/media/File:Chartres_-_cathédrale_-_ND_de_la_belle_verrière.JPG. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021 | Photo by Guillaume Piolle, Public DomainFig. 9 | Jean Calvin on his Deathbed, with Eight Men in Attendance. Lithograph by Jacott, 1850. Wellcome Collection, London. | https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/V0006910/full/full/0/default.jpg. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021 | Photo by Wellcome Collection, CC BY 4.0 Fig. 10 | van Rijn, Rembrandt, Musical Company, 1626, The Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam | https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/collection/SK-A-4674. Accessed 27 Feb. 2021 | Photo by Rijksmuseum, Public Domain

Fig. 11 | Hieroglyphics of the Natural Man and Hieroglyphics of the Christian. Bakewell, J., published by Bowles & Carver. British Museum, London | https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/102734001,

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/image/102755001. Accessed 13 Jan. 2021. | Photo by the Trustees of the British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Literature Review

The following literature review begins by surveying quantitative data regarding current Protestant doctrinal knowledge in the United States. The review continues by providing a synopsis of historical and contemporary catechistic belief and practice from Scriptural, early Church, Reformation, and post-Reformation theologians, philosophers, and academics. Protestantism’s association with the visual arts will also be examined, with a special emphasis on the beliefs and practices of prominent figures during the Reformation. The review moves on to investigate scholarship in the fields of science and education for both how imagery enhances learning and the extent to which it does so. The literature review concludes by evaluating an aesthetic approach for creating contemporary catechetical artwork by considering historical, philosophical, theological, and socio-demographic insights.

Affirmations and Ignorance

From the self-labeled “religiously confused” Stephen Prothero, Professor of Religion at Boston University, comes the revelation that “born-again Christians do only moderately better than other Americans on surveys of religious literacy”—an unenviable statistic that carries right on through seminary, of all places, “where many ministers-in-the-making are unable to describe the distinguishing marks of the denominations they are training to serve” (5-6). Prothero goes on to cite Gallup poll and other survey statistics where Christians of various ages do only marginally better—or even worse—than other demographic groups (31).

Ryan Burgh, who holds a PhD in Political Science from Southern Illinois University and is a lead contributor to the Religion in Public blog, plotted data from both Gallup and the General Social Survey regarding American views on Biblical literacy, with the aggregate showing that over 20% of Americans believe the Bible to be a “book of fables.” Burgh directly associates these statistics with the decline of mainline Protestant churches, which “have traditionally held to the view that the Bible is inspired, but not literal” (“Changing Views”). In a separate article on the blog, Burgh’s associate contributor Paul Djupe, who also holds a PhD in Political Science, cites 2016 survey data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study where practicing members of the LGBTQ community claim to belong to Protestant Christianity; this comprises an obvious non sequitur to any orthodox adherent.

In order to probe Protestant demographic trends with more specificity, it stands to reason that a para-Protestant organization would be at the survey helm—enter The State of Theology, administered under the joint auspices of Ligonier Ministries (one of the foremost conservative Reformed organizations in the U.S.) and LifeWay Research (a subsidiary of LifeWay Christian Resources, the publishing and distribution division of the Southern Baptist Convention). Results from The State of Theology surveys show that although the overwhelming majority of Protestants agree that God is a Trinity of Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, over half also agree with the statement that “Jesus is the first and greatest being created by God.” A subsequent question furthers the contradiction, where nearly half of Protestant respondents agree that “Jesus was a great teacher, but he was not God.” Later questions also reveal a greater-than-50% agreement with “most people are good by nature,” and a 29% disagreement with the statement that “Sex outside of traditional marriage is a sin.”

A contingent of erudite theologians and scholars have cited a loss of catechistic instruction as a primary cause of this spiritual-intellectual quandary. Gary Parrett and J.I. Packer, both distinguished theologians and co-authors of Grounded in the Gospel: Building Believers the Old-Fashioned Way, express in their introduction that “we see catechesis as integral…we mourn its current eclipse, perceiving this as the deepest root of the immaturity that is so widespread in evangelical circles” (10). The authors presently go on to convey the premise of their book—an exhortation for returning to catechetical practice within Christianity:

As we contemplate today’s complex concerns, hopes, dreams, and ventures of Christian renewal, discipleship impresses us as the key present-day issue, and catechesis as the key present-day element of discipleship, all the world over. The Christian faith must be both well and wisely taught and well and truly learned! (17)

The sentiment of these two authors is shared in church pulpits and university lecterns alike. In an article for Scottish Bulletin of Evangelical Theology, Ordained Anglican minister, author, and PhD student at University of Aberdeen Matthew Mason says, “The patristic catechumenate and the Reformation catechism are not the only way of grounding believers in the faith; nevertheless, these doctrinally and biblically rich models stand in striking contrast to the relative lack of doctrinal teaching in the contemporary evangelical church” (209).

Thomas Nettles, former Professor of Historical Theology at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary (a 38-year tenure), also takes up the torch in a 2014 article for The Journal of Discipleship and Family Ministry entitled “An Encouragement to Use Catechisms”:

Suspicion of catechisms as a legitimate tool for teaching God’s Word cannot be justified historically, biblically, or practically…catechizing aims ultimately at the eyes of understanding, heart knowledge…The design of the catechism is, under God, to chase the darkness from a sinner’s understanding, so that he may be enlightened in the knowledge of Christ and freely embrace him in forgiveness of sin. (7, 9).

Finally, in his article concerning catechesis in contemporary evangelicalism for Journal of the Evangelical Theological Society, Clinton Arnold, Dean of the Talbot School of Theology, states “It has become increasingly clear to me that the evangelical church as a whole could benefit from re-examining the testimony of the Church fathers and gleaning insights from how they ministered to new believers” (39).

Based on these testimonies, it appears manifest that catechistic instruction (and the catechism booklets that were created to encompass such instruction) have formed a critical component in Church history for training knowledgeable, devoted disciples, and that the contemporary Protestant Church in the United States suffers because of a deprivation of catechistic education.

Contents of Catechesis

It is important to recognize that catechesis has no singular, typical definition; likely due to the complexity, comprehensiveness, and geographical extent of its employment through the centuries (Parrett and Packer 25-27; Arnold 40-41). However, a brief overview of common catechetical hallmarks will help instill the importance of this lauded pedagogical approach.

Iterations of the word catechesis originate from Greek (and later, Latin) verbs revolving around the concept of listening, teaching, and instructing (specifically, the Greek words katēchein, katecheo, and kateleo, and the Latin catechismus) (Arnold 40; Potgieter 2; Parrett and Packer 25). Raymond Potgieter, faculty of theology at North-West University in South Africa, notes that in its original context, the concept implies “word of mouth teaching” (2): the oral nature of early catechesis is agreed upon throughout the consulted scholarship (Parrett and Packer 26; Williams 21; Arnold 45-46). The teaching of catechumens was carried out predominately by trained theologians, and the process was lengthy and rigorous, often lasting three years (Arnold 42-45).

Potgieter states that catechisms (a term which can be used for the holistic process, not only for booklets containing catechetical writings) were intended as a “means of religious instruction preparing catechumens including children and adults for confirmation of their Christian faith” (2). In his article “The Future is Behind Us: Catechesis and Educational Ministries,” Darwin Glassford, Director of Online Learning and Graduate Program Director at Kuyper College, states that catechesis is defined by “passing on a fixed body of knowledge the learner (catechumen) is expected to learn” and is also “holistic, concerned with the learner’s (catechumen’s) knowledge, affections and lifestyle” (S-176). Daniel Williams, Professor of Patristics and Historical Theology at Baylor University, echoes Glassford’s description, saying that the catechumenate entailed “a series of steps that leads the new believer to baptism and a deeper knowledge of the faith” which included “ethical and theological exhortations” (21). Williams describes the contents of catechesis as arising organically out of “situations of need” (such as apologetic defenses against heresy) and consisting of expressions of the early Church’s faith (all centered on Scripture), namely, “Bible commentary, creedal statements, doctrinal explanations, hymns, and so on, which articulated in a few words a basic understanding of the Christian Bible and its profession” (21-22). Summarizing such-like descriptions, Arnold lists four key features of early church catechesis: first, immersion in the Word of God, second, teaching central doctrines of the faith, third, spiritual and moral formation, and fourth, deliverance from demonic influences (46-54). Centuries later, catechesis became more standardized in written form, often referred to specifically as a “catechism,” and containing at least three primary elements: the Apostle’s Creed, the Lord’s Prayer, and the Decalogue, although additional material was often included, such as a lengthy question-and-answer format of doctrinal instruction (Parrett and Packer 26, 156, 160, 174; Potgieter 2-3; Hollon 4; Nettles 7-8).

Calls to renew catechesis and a general description are well and good, but a Protestant might argue “what about Sola Scriptura?” Does the practice find definitive substantiation in the words and writings of the Reformers, or early Church Fathers, and especially, within the Bible itself? Where did this idea of catechesis come from, who has used it, and why has present-day Protestantism within the United States largely abandoned it?

Historical Catechesis

The obvious and most crucial source of validation for catechesis is the Bible.

Holy Scripture sets the precedent, and the verb itself—derived from the Greek word katēchein occurs eight times in the New Testament (Glassford S-176).

Thomas Nettles writes “Scripture itself encourages the use of catechisms in our efforts to be transformed by the biblical message…Examples or models of instruction used by the first-century church abound in Scripture, both in method and content” (13).

Parrett and Packer devote an entire chapter from their book—aptly titled “Catechesis Is a (Very!) Biblical Idea”—to affirming the Scriptural precedence for catechesis.

writing from a Methodist perspective in their essay for the Christian Education Journal, Benjamin Espinoza and Beverly Johnson-Miller (the latter Professor of Transformative Education and Aging at Asbury Theological Seminary) cover the same material as Nettles and Parrett and Packer regarding the Scriptural preeminence of catechesis. Espinoza and Johnson-Miller conclude their segment by positing “The biblical precedent suggests that catechesis is relevant and necessary for anyone who looks to Scripture as the source or guide for faith. Catechesis is a comprehensive process of Christian initiation and growth” (17).

Next to Holy Scripture, the practices of the ancient Church, as recorded in the writings of the Early Church Fathers, have carried a prodigious authority and influence throughout the history of Christianity.

Daniel Williams succinctly proffers that “The practice of a catechumenate…was created by the early Fathers” (21)

Potgieter, for his part, refers to John Chrysostom and Hippolytus of Rome and their emphasis within catechesis on the definite, consistent practice of Christian principles within individual and family life (2).

Clinton Arnold stresses the priority that Church Fathers placed on teaching new believers. He includes a list of eminent names that “devoted themselves” to the instruction of converts, men such as Origen, Clement of Alexandria, Pantaenus, Tertullian, Hippolytus, Ambrose, Cyprian, Gregory of Nyssa, John Chrysostom, Theodore of Mopsuestia, Cyril of Jerusalem, and Augustine (45).

Protestants, by and large, place immense value on the positions taken by the original Reformers, especially Martin Luther and John Calvin.

Potgieter declares that “Protestant heritage is synonymous with the traditional employment of catechisms and catechetical teaching of both young and old…Although not a new concept at the time of the Reformation, it became a standard for religious instruction” (1-2).

Matthew Mason continues by identifying Reformers as well, saying “A similar inventory of sixteenth and seventeenth century theologians could be made, including Luther, Calvin, Ursinus, the Westminster Divines, Richard Baxter, and John Owen” (209).

Thomas Nettles goes so far as to describe the Reformation as the “Golden Age” of catechisms (7-8).

Gayle Felton, the late assistant professor at Duke Divinity School and Meredith College, relates how John Wesley began to catechize North American children regularly while in the colonies in the early-mid 1700s and subsequently constructed his own catechism. He urged the use of this catechism by all Methodist preachers and Methodist households (97, 99).

Contemporary Catechesis

In his article’s introductory comments, Thomas Nettles, a stalwart Baptist, speaks of the way his own denomination tends to view catechesis, saying “Many contemporaries have a deep-seated suspicion of catechisms. In our own Baptist denomination, many would consider the words ‘Baptist catechism’ as mutually exclusive (6).

Parrett and Packer echo this sentiment from within the Reformed tradition, saying “It will doubtless surprise a good number of evangelical Protestants to hear that catechesis is not only a biblical idea, but a very biblical idea. Many of us—especially those of us who grew up in North American Evangelical cultures in recent times—rarely if ever heard the words catechesis or catechism” (31).

Stephen Prothero gives voice to another concern, clear to most orthodox Protestants, by noting that liberal theology is still flourishing—“Confessional Christians…seem to be a voice crying in the wilderness. As the nation has migrated from understanding itself as Protestant to understanding itself as Christian, then Judeo-Christian, and then Abrahamic, many have jettisoned (in the name of tolerance) the great teachings and stories of the Christian tradition” (120).

Matthew Mason references other scholars who have pronounced that doctrine is notably absent from the life of modern Christians before adding his own insight that “evidence for this absence of doctrine is the neglect of serious catechesis in evangelical churches” (208).

Clinton Arnold also articulates that modern evangelical churches “…place a minimal emphasis on the training of new believers, especially when compared to the prominence and importance of the catechumenate in the ancient church” (44).

Espinoza and Johnson-Miller posit that a modern over-reliance on developmental theory has left behind “sixteen centuries of church history” in which theology proper held the principal position of making mature believers who are spiritually and mentally healthy, whole, and growing (9, 12-13).

In catechesis’ contemporary absence, Sunday schools, still replete with the vices already mentioned, continue to dominate (Parrett and Packer 22).

As recently as 2012, Darwin Glassford’s article for Christian Education Journal states that “Sunday schools have usurped parental and congregational responsibility for teaching the Scriptures…If one is willing to take a hard look at a church’s formal education programs, including Sunday school/Church education, it becomes clear they have not delivered on their promises” (S-174, S-178).

Parrett and Packer include in their book a fairly concise list that encompasses nearly the whole of what has been said to this point, and so will serve as a fitting conclusion to this section:

- Catechesis is a thoroughly biblical idea and practice, and we (that is, the evangelical movement as a whole) have strayed grievously from the mandates and model of Scripture in this regard…

- The practice of rigorous catechesis has proven to be essential and effective at numerous critical junctures in the life of the church and there is much to be learned from this history for ministry in contemporary contexts today…

- Many forces have conspired to distract most of today’s evangelicals from the biblical business of catechizing, and there are significant consequences that have resulted from our failures in regard to this ministry…

- Happily, there are a number of contemporary efforts under way to renew catechetical ministries. These are worthy of our serious observation and, in some cases, emulation…

- Catechesis involves instruction that is both ancient and essential. It focuses on the primary doctrines of ‘the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints’ (Jude 3), and especially upon the glorious Gospel of the blessed God. Thus it aims to celebrate and preserve the unity of the church…

- Catechesis involves instruction that is holistic. It touches the entire person (and the entire community)—head, heart, and hands; doctrine, experience, and practice…

- Catechesis involves instruction that is highly relational and interactive. It is a ministry of the church and must be carried on in the context of the community of faith.

- Catechesis involves instruction that is timely and culturally relevant. This ancient faith must always be presented vis-à-vis those alternative claims regarding truth, worldview, and lifestyle that dominate the age and culture in which the church lives…

- Catechesis involves instruction that is foundational for faith development throughout one’s life. While catechesis is often associated (and rightly so) with grounding persons in the basics of the faith, it also envisions practices for ongoing learning upon and within those very foundations that have been laid. (28)

The various other catechetically-focused sources referenced in this literature review all strongly support Parrett and Packer’s synopsis; however, much has changed in the 400-some-odd years since the Reformation—to say nothing of the 2,000-give-or-take since Scriptural exhortations to catechesis. How might transformations in culture (especially with the advent of modern technology) affect a catechetical approach?

Visual Learning

One important cultural shift that has considerable relevance to the implementation of contemporary catechesis is the move away from primarily text-based learning towards increasingly visual learning. Society is inundated by images, especially by way of technology, and the ubiquitous nature of screens only compounds the cognitive effects of this educational shift.

The rise of visual learning and a visual culture has led to a vast quantity of scholarship that spans an extensive array of concepts. However, the ideas of technology being a major contributing factor to this rise and the steadily increasing importance of “visual literacy” were both consistently foundational principles. A group of Australian academics including Judith Dinham, Associate Professor and Director of Learning and Teaching in Curtin University’s School of Education, summarize this position in their article “Visual Education – Repositioning Visual Arts and Design: Educating for Expression and Participation in an Increasingly Visually Mediated World” by describing how “New visual technologies and related multi-modal forms of expression and communication are transforming our society. There is a move from the text as the dominant mode of communication and expression to an increased use of the visual” (78).

Connie Malamed, author of Visual Language for Designers: Principles for Creating Graphics that People Understand and founder of an eponymous consulting company specializing in visual instructional design, states that as “the quantity of global information grows exponentially,” individuals “depend on visual language for its efficient and informative value…We often find that technological and scientific information is so rich and complex, it can only be represented through imagery” (10). She finishes the paragraph by saying that “The sheer quantity of visual messages relayed through new technology has led some to call imagery ‘the new public language’” (10).

The Church Universal has a rich history of visual pedagogy. Until the Reformation, images had been copiously and unabashedly incorporated into the public and private life of the faithful since nearly the beginning of Christianity (two periods of iconoclasm split between the 8th and 9th centuries conspicuously excepted). Celia Chazelle, Professor of early Medieval history at Yale, gives a detailed account of the instructional use of artwork circa 599-600, examining two letters written by Pope Gregory the Great (these letters are prevalent within arguments in favor of Church art, and for good reason). In his enormously famous statement (though often misquoted), Pope Gregory articulates his apologetic for imagery as an educational device for the illiterate, saying “‘For a picture is displayed in churches on this account, in order that those who do not know letters may at least read by seeing on the walls what they are unable to read in books’” (qtd. in Chazelle 139). Chazelle notes that the specific artwork under discussion were large narrative paintings of Bible stories located in a church building, and that the illiterati who viewed them would have been in a context where the stories and their meanings would have been explained (139).

A few centuries later, and the pedagogical use of religious art had only increased. In his seminal work A Universe of Stone: A Biography of Chartres Cathedral, author Charles Ball minutely examines the multiplicity of methods by which the artistic program at Notre Dame de Chartres carefully and comprehensively teaches Church history and doctrine (Chartres, because of its high level of preservation, can stand as an archetype for medieval cathedrals overall—and there were many).

In his book The Forge of Vision: A Visual History of Modern Christianity, David Morgan, Professor of Art, Art History, and Visual Studies at Duke University’s Trinity College of Arts and Sciences, gives an introductive summary to common perceptions of Protestantism’s general relationship with images:

“It is often said that Protestantism has no place for images. In fact, Protestants have virtually always made use of images in one way or another. Yet the view persists that Protestantism is aniconic. This probably depends on several things. One may be the tendency among many Protestant groups to avoid imagery in worship settings, though rarely in the home, school, or everyday life. Another reason is likely the episodes of iconoclastic riots in the 1520s in Germany and Switzerland, and in the Netherlands and England a few decades later” (42).

Sergiusz Michalski’s book

expounds on the tension between Reformers and artwork. Michalski probes the conflict by examining four central Reformers; however, the legacies of just two, Martin Luther and John Calvin, principally define the opinions and standings of many Protestants today. To rather brusquely condense Michalski’s discussion, Martin Luther was frequently ambivalent on the use of images, both in the private sphere and in public places of worship.Although writing negative-leaning positions (in one instance specifically due to the Catholic Church’s tendency towards opulence), Luther also “defiantly” opposed the removal and destruction of artwork from churches and decried an iconoclastic exegesis of the second commandment. Throughout his ministry, Luther vacillated regarding the employment of images: his stances depended on the context in which artwork was used and the presence of external factors affecting Luther at different periods in his life (5-11).

John Calvin, on the other hand, is closely aligned with iconoclasm. He correlated a serious array of sins with the use of religious imagery, from condemning much artwork as idolatrous (due to his exegesis of the second commandment) to the inclination of humanity towards pride via external grandeur (Michalski 65). Morgan further reveals that Calvin held and promulgated the misconception that the early church—“‘during which religion was in a more prosperous condition, and a purer doctrine flourished’” (qtd. in Morgan 43)—was entirely aniconic (43). Calvin appears to go so far as to explicitly discredit Gregory the Great’s exhortations to instruction through art, the Reformer seeing “practical theology” as a non-starter for serious theological dialogue (64).

Amid these frankly paradoxical perspectives, the utilization of instructive religious imagery during the Reformation continued—and, mostly under the auspices of Lutheran theology, even flourished. David Morgan describes the Protestant use of artwork as a shift in “economies”; namely, rejecting the personal (and often transactional) interaction with pictures in the various acts of veneration within Roman Catholic practice to an “ambitious traffic of sacred information. It was no longer what you offered or gave up that secured divine favor, but what you knew that counted.” (Forge 49). The author further categorizes this “sacred information” by presenting “several forms and places that collectively map out the Protestant life-world” where pictures and “visual practices” would subsist (51).

Two specific examples are given by Lori Ann Ferrell, Dean of the School of Arts and Humanities at Claremont Graduate University, and Bonnie Noble, Associate Professor of Art History at UNC Charlotte. The former discusses English theologian and staunch Protestant William Perkins’ book A Golden Chaine, which contained a chart visualizing the doctrine of predestination. Ferrell states that “By putting this busy visual complex to work, the imagery does not merely illustrate Perkins’s theology but actually provides a complete, one-page précis of an extensive, complex doctrinal treatise (601).” The latter writes at length about Lucas Cranach, artist and intimate friend of Luther himself. Noble says that the Cranach “made the reformer’s complex ideas intelligible to a wide range of viewers” (1).

Despite convolutions from certain strains of Reformed teaching, the belief and practice of Protestantism, both during and after the Reformation, do align with the historical church in broad approval of pedagogical religious imagery. Robin Jensen, the Patrick O’Brien Professor of Theology at Notre Dame University, beautifully articulates this assertion when she says that “the Reformed church always has had a place for the arts, even in communal worship. But, given both history and continuing tradition, the place of art (especially visual art) needs to be understood and managed, both faithfully and sensitively. Thus, the central question is, not whether, but how Protestants should incorporate art in liturgy.” (“Arts” 362). Returning the discussion to the contemporary context, what does current research from the fields of education and life science have to say regarding the effectiveness of visual illustrations on comprehension and retention in general?

Visual Learning Cont...

That visual illustrations promote learning is a fact almost beyond disputation; however, the exact manner by which imagery assists education is not known exactly, with several viable options on the table (and of course, they could also work together in varying proportions).

In facilitating comprehension of textual information, Levie and Lentz supply a list of methods. First, illustrations can provide a context for understanding written material. Second, pictures can challenge viewers to analyze words and their meanings more carefully. Third, imagery can keep disparate components of complex information in a readily accessible relationship, enabling the learner to process other aspects more easily. Last, visuals can afford a concrete method for verifying understanding of the text (220-222). The authors go on to convey a range of possibilities regarding how illustrations aid retention of information as well. These options include simple repetition (redundancy of what the text articulates), the creation of vivid mental pictures (invoking the imagination), and a few theoretical approaches including the levels-of-processing approach and dual-coding (222-223).

Dual-coding theory appeared promptly in the research, with Parrish and Aisami both referencing the concept. (“Instructional”; 538) Dual-coding theory was conceived by Allan Paivio. Both Cual-Coding Theory and Multimedia Learning Theory, preferred by Richard Mayer, describe systems wherein instruction is presented through words (either written or spoken) along with pictures (either static or dynamic); the learner then develops his or her own mental representations of the concept at hand. The theories share a foundationally bimodal concept of how the human mind works. In these theories, two information processing frameworks work concurrently: one for verbal data and one for visual data (Mayer 6; Paivio 53-54).

When designing for education, both rational and emotional aspects must be taken into account, as Dennis West, of Brigham Young University’s Department of Instructional Psychology and Technology, and his co-authors articulate three ways in which graphics catalyze affective learning, first, through commanding interest (a learner’s mental focus), second, by holding attention (enabling greater informational extraction), and third, via increasing engagement and motivation (the desire to learn and persist in the learning experience) (West, et al.).

Malamed repeats the rational and cognitive bypass created by affective graphics and further notes that brain research has validated emotional responses to “both pleasant and unpleasant pictures,” which, even after repeated exposures, elicited “pronounced brain activity that does not occur when [the participants] look at neutral pictures” (a phenomenon which continued despite an absurd amount of repetition) (202-203). Observers also spend more time looking at these sorts of affective images in contrast to their neutral counterparts (202). Malamed asserts that “meaningful emotional content” captures attention and interest “because [these graphics] generate a state of arousal, which is a cognitive and biologically energized state. As a general rule, most people find monotony and boredom to be an unpleasant experience and stimulation and activation to be a pleasant experience…Emotional experiences help people achieve and maintain this optimal state of arousal” (207).

Throughout the history of Christian art, the physical appearance of artifacts has varied considerably. In Chartres Cathedral, both sculpture and colored glass reveal doctrine and the history of the faith (Ball 171)—the architecture itself, in its thoughtful and beautiful crafting, can certainly be listed under the heading of pedagogic art as well. Pope Gregory, in his letters to the bishop of Marseilles, discusses large narrative paintings within churches that depicted the deeds of holy people (Chazelle 141). Ferrell gives examples of early Protestant infographics included in a theological tome, going so far as to claim the pictures are more effective and concise than the literary work itself (601-604). Lucas Cranach completed paintings and altarpieces that borrowed from traditional Roman Catholic formats to reinforce Lutheran theology (Noble 1). Even the iconoclastic Calvin himself condoned paintings, engravings, and other images in certain genres (mainly for educational merit, and only if they were displayed in non-religious contexts) (Michalski 70-72).

As demonstrated, the imperative of Protestant imagery from the time of the Reformation was instruction in the Holy Scriptures: Biblical text was preeminent within the auspices of theology-philosophy, and pictures were supplementary (at best). In the context of a twenty-first century Protestant catechesis, an educational goal necessarily remains central. Therefore, current insights from the realm of instructional design will provide guidance for a creative approach.

For constructing an influential visual educational presentation, West, et al. proffer a list of foundational items, including font choice, which affects readability, emotional impact, and visual clarity; color selection, which influences message (through mental associations), emotion, and enhances visual language (aiding in navigating the picture and interpreting meaning); organization, which guides the eye, increases attention and understanding, and diminishes confusion; iconography, those signs and symbols that cultivate interest, impact emotion, and impart cultural associations; and theme, which organizes all graphical elements into a unified whole and can “cement the message of an instructional object.”

Parrish also expounds numerous means by which illustrations can be effectually incorporated with text, from simplified graphics intended simply to grab attention, to photographically naturalistic images, to complex and annotated diagrams (“Instructional”). He also clarifies when and where certain pictorial approaches can be more helpful. For example, complexity can draw and hold a viewer’s attention, but the artist must be careful not to overdo complexity to the point of bewildering the eye, which would cause an observer to retract his or her gaze. Similarly, the novelty of something new or unexpected entering a viewer’s sensory field commands attention; however, overuse degrades novelty into monotony. The author further articulates the unique value of illustrations in teaching abstract information “by providing images that learners might not generate on their own.” Such imagery might include “Charts showing trends, diagrams of processes, and visual metaphors of abstract ideas” (“Instructional”). Levie and Lentz add a caveat along these lines, stating that “Maps, diagrams, and graphic organizers appear to be less reliable than representational pictures. Some research suggests that a major problem with non-representational pictures is that learners are not practiced in making effective use of them” (218). Similarly, both Malamed and West, et al. stress the importance of a viewer’s familiarity with iconography or symbolism employed in an instructional context; the latter authors recommend a legend to orient an audience who might not be well-versed in the necessary visual language (Malamed 37; West, et al.).

Connie Malamed expresses how artists can accurately communicate their intended message by utilizing sound principles within instructional design, achieving goals as varied as process explanation, emotive response, or data visualization (9). This is achieved foundationally by “directing the cognitive and emotional processes of the audience” (14). In the second portion of her book, Malamed catalogues principles for accomplishing these objectives.

Returning to the history of pedagogical imagery within Protestantism, as intimated, literary centrality combined with the desire for reproducibility on the printing-press seems to have frequently relegated the actual appearance of instructive artwork to a second-class status. Of course, many masterpieces were created within Protestantism during the Baroque era (Rembrandt’s oeuvre being a foremost instance), with straightforward Biblical narratives comprising a large segment. Beginning mainly with the Dutch Golden Age, the category of genre scenes (along with still-life) gives a tolerable exemplar for combining attractive imagery with education outside of Scriptural portrayals. Genre pieces “depicted scenes from everyday life, both high and low” (Meagher) and often “offered clear moral guidance on how to live a pious life” (Collins). Lessons could be presented wittily, morbidly, plainly, covertly, et cetera, but of note within this genre is artworks’ objective beauty. According to Jennifer Meagher, Senior Collections Cataloguer of European Paintings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, “genre painting in the Low Countries remained richly diverse in both style and subject as artists achieved new heights of technical refinement, optical and perspectival sophistication, and an often superb evocation of mood.”

The lucid combination of teaching and aesthetic present in such genre scenes segues into one rather understated aspect of Protestant art within the historical portions of the scholarship: discussion of pictures’ visual appeal—their beauty. Although this concept does appear in the purview of instructional design, a more holistic understanding of beauty also provides an important counterbalance to dictums from that field. The late Sir Roger Scruton, an English philosopher, author, and speaker who specialized in aesthetics, made this topic (sans overt denominational slant) the focus of his book

. Scruton sets the stage by presenting an important (though by no means exclusive or undebated) historical understanding of beauty: that it is an “ultimate value—something that we pursue for its own sake, and for the pursuit of which no further reason need be given” (2). The two other concepts in the category of “ultimate value” are truth and goodness; altogether they comprise “a trio of ultimate values which justify our rational inclinations” known as “transcendentals” (2). The author notes that this model of thinking extends at least back to Plato and was later adapted by Christian theologians as attributes of the Triune God (2-3).

Philip Graham Ryken, eighth President of Wheaton College and author of the booklet Art for God’s Sake: A Call to Recover the Arts, speaks of both the importance of beauty within the arts and its broad-scale abandonment in modern culture, both secular and Christian. Ryken prodigiously stresses the importance of artistic excellence, stating that work which matches the description above “Ultimately…dishonors God because it is not in keeping with the truth and beauty of his character”; he asserts that a robustly Biblical understanding of the arts “is important not just for artists, but also for everyone else made in God’s image and in need of redemption.” Scruton himself focuses on the abandonment of beauty and embrace of ugly in chapter 8 of his book. Like Scruton, Ryken refers to goodness, truth, and beauty as essential criterion for art and highlights beauty as being expressly connected to God’s divine character. However, unlike Scruton, Ryken is forthcoming in his personal declaration of Biblical, Trinitarian orthodoxy when pronouncing beauty as an end-in-itself beyond mere functionality.

Robin Jensen also discusses the centrality of beauty within Christian practice of the visual arts in her article “The Arts in Protestant Worship.” She refers to Augustine as following Plato in underscoring the capacity of beauty in the physical universe—both in nature and in human creations—to draw a person to “the ultimate source of beauty” (which Augustine located in the Trinity) (363). An individual’s eternal position can be directly affected through this ascertainment and pursuit of beauty.

An aesthetic consideration closely related to beauty focuses more on the two other classical transcendentals, goodness and truth, in a way which might be defined as “redemptive.” Philip Ryken wonderfully enunciates a Christian view of ideal art by referencing the transcendentals, standards which “are not relative; they are absolute,” and it is from Ryken’s lengthier description that the term “redemptive” has been drawn. Ryken expresses it this way:

Modern and postmodern art often claim to tell the truth about the pain and absurdity of human existence, but that is only part of the story. The Christian approach to the human condition is more complete, and for that reason more hopeful (and ultimately more truthful). Christian artists celebrate the essential goodness of the world God has made, being true to what is there. Such a celebration is not a form of naive idealism, but of healthy realism. At the same time, Christian artists also lament the ugly intrusion of evil into a world that is warped by sin, mourning the lost beauties of a fallen paradise. When truly Christian art portrays the sufferings of fallen humanity, it always does so with a tragic sensibility…There is a sense not only of what we are, but also of what we were: creatures made to be like God.

Even better, there is a sense of what we can become. Christian art is redemptive, and this is its highest purpose. Art is always an interpretation of reality, and the Christian should interpret reality in its total aspect, including the hope that has come in the world through the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Rather than giving in to meaninglessness and despair, Christian artists know that there is a way out. Thus they create images of grace, awakening a desire for the new heavens and the new earth by anticipating the possibilities of redemption in Christ. (Ryken)

A distillation of the scholarship in the vein of an appropriate artistic approach within modern Protestant catechesis can be stated quite concisely: a vast deal of leeway exists for the appearance of visual illustrations. As West, et al. describe it, “there is no simple formula that can be used to design or select visuals that improve learning and performance in all situations.” One of the more consistent elements evident in the research was the idea that art cannot instruct in a vacuum—the viewer must be informed via additional means, either previously to or in simultaneity with looking at pedagogical artwork. Even within Pope Gregory’s famous description of pictures being displayed in churches “in order that those who do not know letters may at least read by seeing on the walls what they are unable to read in books,” Chazelle carefully notes that Gregory never offers approbation to the idea that illustrations can teach a viewer who is entirely ignorant of the content depicted (138-139). Several additional items that rose to the fore included conceptual clarity (engaging both cognitive and affective domains), a close physical proximity between text and picture (with special emphasis on the primacy of Scriptural passages), the necessity for a work of art to have an attractive aesthetic and redemptive tenor (which might properly be labeled beauty), and an ability to be mass-produced (for purposes of evangelism and discipleship). Historical instances of these qualities were further investigated in the case study and visual analyses included just a bit further on.

Literature Review Summary & Knowledge Gap

The aggregated research surveyed supports the original hypothesis: in the modern era, many self-proclaimed Protestants in the United States either do not know or do not understand foundational dogma, and a major factor of this ignorance and misapprehension is a lack of catechetical instruction. Despite vigorous acclamations for catechesis by a vast number of prominent historical theologians—scriptural, ancient, and Protestant alike—anti-authoritarianism, liberal theology, and lay-led gatherings (such as Sunday schools and small groups) have been major factors steering the vast majority of contemporary Protestant churches in the U.S. to abandon catechistic pedagogy. The result is an array of intellectually and spiritually moribund Christians (or pseudo-Christians).

Currently, a return to catechizing is being called for by intelligent, wise, and eminently Godly individuals from most, if not all, strains of Protestantism. However, while calls for a return to catechistic learning within contemporary Protestantism in the U.S. certainly do exist (albeit in the minority), these sources appear to focus almost exclusively on a traditional, literarily-driven approach, giving little page-space to multimodal learning in general and nearly none whatever to visual illustrations in particular within catechistic methodology (excepting a handful of children’s resources). It does not appear that a 21st-century catechism has been robustly explored that incorporates either insights gained from modern scholarship in visual cognition and pedagogical theory or historical and recent apologetics for imagery from the ambit of theological and philosophical aesthetics. This lack might be due in part to Protestantism’s occasionally strained relationship with pictures, resulting from the iconoclastic positions of some Reformers; the primacy of a literary presentation is also understandable given the written word’s historical precedence (in both western religions and academia). But modern culture’s reliance on and obsession with visual stimuli cries out for an aesthetic reassessment. Recent data concludes that a combination of imagery along with text or verbal information increases understanding in both the short and long-term; therefore, by implementing visual presentations as a foundational part of catechistic learning, comprehension and retention can be amplified through activating multiple learning domains. Successful illustrations within a modern Protestant catechetical context could assume a variety of aesthetic styles; however, several shared foundational elements are underscored by robust scholarship: conceptual clarity that invites further dialogue, scriptural immediacy, objective beauty, and easy reproducibility.

Case Study

Religious art from workshop of Lucas Cranach the Elder presents a seminal historical instance of utilizing imagery to present Protestant theology-philosophy. Lucas Cranach often worked directly with Martin Luther (Noble 1), so the artist and those within his workshop were naturally among the first to interpret Protestant doctrine into visual language, “[making] the reformer’s complex ideas intelligible to a wide range of viewers” (1). Therefore, studying the artwork that Cranach himself fashioned (or directed others to fashion) will provide valuable insight for guiding artistic decision-making for this genre of picture. The knowledge gained will inform a strong visual concept for contemporary catechesis, and also place newly crafted pedagogical imagery firmly within the tradition of its Protestant antecedents (Morgan, Forge 9).

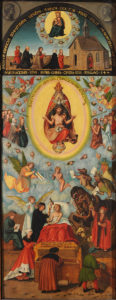

The first Cranach image to be examined is the painting Der Sterbende—known by a few slightly varying names in English but all containing The Dying—that actually precedes the widespread traction of Lutheran theology and practice (Ozment 85). In the image, a dying man is lying in bed surrounded in the foreground by several human figures, including a doctor, a person writing, and a clergyman with crucifix, among others. In the background, however, are a plethora of supernatural persona, from terrifying demons on one side, to angelic beings on the other, to the Holy Trinity, encompassed by a prismatic mandorla and surrounded by redeemed souls, apostles, and cherubs. Above all these, and in a distinctly separate space, a group of churchgoers kneel to pray outside the church-building while the crowned Virgin hovers above them in her own mandorla (replete with clouds and putti). Woven throughout both scenes are lines of text, a prominent feature of Protestant art that Michalski states came about “as an autonomous artistic phenomenon” (41).

The late Steven Ozment, former McLean Professor of Ancient and Modern History at Harvard University (and Professor Emeritus), describes the painting as “present[ing] a more distinct Lutheran message. It depicts the ‘Wrath of Hell’ that awaits the delivery of a dying man’s soul, whose failings over a lifetime are tallied by background monsters who wait to devour him” (85). The dichotomous composition of the lower half, which would also feature in Cranach’s Law and Gospel, starkly reveals the only two possible endings for the dying man: damnation on the one hand (because he has transgressed God’s commands), or eternal life on the other (if he but repents and seeks forgiveness from God) (Ozment 85). Bonnie Noble’s interpretation of the image slightly contrasts that of Ozment, in that Noble regards Der Sterbende as giving approbation to salvation by works (after all, an angel in the scene does hold a placard literally reading “good works”): a doctrine that was certainly antithetical to Lutheran theology (39-40). Noble emphasizes her stance by translating and highlighting the inscription at the foot of the bed, which reads “‘You must despair, because you neglected God’s commandments, and fervently fulfilled mine [the devil’s] with the help of the woman [Eve]’” (40). However, the author does not address the inscription just above the head of the bed, which translates roughly to “I ask you to repent of sin and trust compassion”; a statement that would seem to lend credence to Ozment’s view. (It also certainly appears too late for the dying man to perform any good works.) Concerning the various other lines of text scattered around the composition, Noble relates that they include Psalm 144 (in the Latin Vulgate version, which corresponds to Psalm 145:9 in Luther’s translation) and other supplements and identifiers for the pictorial motifs (40). She additionally notes that the inclusion of Latin verses here signifies a crucial distinction between this painting and Law and Gospel, “where the appended Bible verses and…labels are in German,” because “Luther’s German translation of the Bible is one of the cornerstones of his theology and the basis of sola scriptura” (40).

Fig. 12 | Lucas Cranach the Elder, Der Sterbende (The Dying Man), 1518, Museum der bildenden Künste, Leipzig | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Der-Sterbende-1518.jpg. Accessed 29 Nov. 2020 | Photo by Trzęsacz, Public Domain

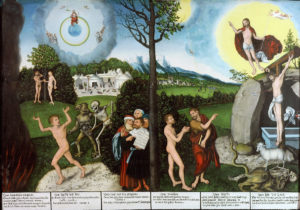

Cranach’s most famous painting must certainly be Law and Gospel, located in the Schlossmuseum in Gotha, Germany. Produced by Cranach around 1529 and informed by active discussions with Martin Luther, Bonnie Noble describes the piece as “the first definitively Lutheran painting” and asserts that “Cranach’s identity as a Reformation artist is linked inextricably to [this] pictorial type” (29, 270). Noble further claims that the uniqueness of the “Law and Gospel” visual concept (Cranach created multiple iterations with slight compositional changes) lies in the fact that it “does more than merely reiterate key notions of Lutheran theology. In its form, iconography, and function it differs markedly from art of the preceding period” (27). Michalski echoes this sentiment, declaring Cranach’s illustrations on this theme “the most important new Protestant iconographic formulation,” and stating that this painting (along with its twin located in Prague), “disseminated [the Law and Gospel/Grace] motif throughout Reformation Europe” (34).

As in Der Sterbende, the compositional arrangement of Law and Gospel is divided strictly in half by an unusual tree in the closest foreground: it is half-alive and half-dead. As the viewer looks at the painting, the dead, left half of the tree overlooks a rather chaotic landscape that includes Old Testament Biblical narratives (namely, the Bronze Serpent and the Fall) and a grotesque allegory where a nude man is being prodded into hellfire. Near the tree, a small cluster of figures stand around a man in 16th-century attire holding tablet of stone inscribed with the Ten Commandments. Above all these elements, Christ sits astride the earthly globe in judgement, adored by saints. The right, living side of the tree stands before a more positive (though no less surreal) vista, where Elijah, who grasps a large book, can be seen pointing a another nude man’s gaze towards the crucified Christ. A stream of blood sprays from Christ’s side onto the nude figure, and the Holy Spirit dove flies along this crimson path. At the foot of Jesus’ cross, a lamb, holding a banner of victory, stands astride a skeleton and a demon. In the midground behind the crucifixion, the empty tomb stands open with the risen Christ, also bearing a victory banner, hovering just above. The distant background shows a contemporaneous town with an anachronistic annunciation to the shepherds occurring in the fields before it. Underneath the combined whole, a white strip of panel displays six columns of Scriptural text in German.

Noble summarizes the overall program of the painting succinctly, “Law and Gospel explicates the defining point of Luther’s theology, the idea of salvation by faith alone” (35). Furthering this model of a Lutheran apologetic, she also describes how the Law and Gospel motif visualizes the three famous Reformation sola slogans in opposition to Catholic belief and practice: instead of illustrating a single Scriptural text, Law and Gospel serves to narrate a broad concept (35-36). Although Noble recognizes that strictly typological interpretations of the image have been articulated, she casts doubt on that methodology by referring to the inclusion of Christ in Judgement on the “Law” side of the painting and also, in later version of Law and Gospel, the Brazen Serpent on the “Gospel” side (36-37). Of Christ in Judgement, Noble says that “[Its placement] on the law side tells us that Law and Gospel presents not Old Testament against New Testament, or type against antitype, or even law against gospel but, rather, the distinct and simultaneous relationships, both judging and merciful, of God to humanity” (37-38). Similarly, the Brazen Serpent’s “inclusion… on the gospel side in post-1529 versions of Law and Gospel emphasizes that grace exists in both the Old and New Testaments, just as judgment exists in both Testaments. Moreover, because it appears on the grace side of the composition, it demonstrates that the law and gospel coexist throughout scripture, even as they remain distinct” (38).

Fig. 13 | Lucas Cranach the Elder, Law and Gospel, oil painting, 1529, Herzogliches Museum, Gotha | https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:GOTHA-cranach-veljo.jpg. Accessed 29 Nov. 2020 | Photo by Szepec-571, Public Domain

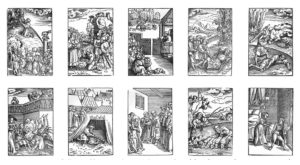

Last, but certainly not least, are Cranach’s didactic woodcuts, taken as a group. Despite being mass-produced and comprising a wide variety of subjects, Bruce McNair, Professor of History at Campbell University, still echoes Noble’s earlier statement about intelligibility, describing the woodcuts as “intended to teach complex ideas in easily accessible ways” (41). Henk van den Belt, Professor of Reformed Theology at the University of Groningen, says that the woodcuts used in Martin Luther’s Deudsch Catechismus became “very influential in Lutheran catechetical tradition,” even though they were “not very impressive from an artistic perspective” (196).

In an article about the illustrations for the Ten Commandments, van den Belt articulates that the pictures, as originally employed by Luther, were accompanied by a concise amount of text: namely, the commandment itself and one brief question and answer expounding on the commandment in simple terms.

Apparently, the illustrations originally functioned as a visual tool underlining the message of the commandments. For the illiterate, these paratextual elements probably were aids to help them remember the words which most people in sixteenth-century Germany would have learned by heart as a child. The illustrations undoubtedly helped the children to memorize the text of the catechism as an explanation of the Ten Commandments. (198)

The decalogue woodcuts also used exclusively narrative scenes from the Old Testament as subject matter—which van den Belt labels an instance of Reformation “iconographical renewal,” since portrayals of the Ten Commandments throughout the Middle Ages utilized secular scenes (205-206). The author connects this renewal in with the Lutheran theological emphasis of Law and Gospel, where the Old Testament is inextricably linked with the Law, being a preparation for the Gospel (200). Another theological insight from van den Belt, which ties into the previous idea, is that all Ten Commandment illustrations (except one) highlight punishment for sin, which is another Lutheran emphasis, as “The Law confronts us with sin and its consequences in order to lead us to Christ” (201).

In another article, Bruce McNair looks at Cranach’s woodcuts for the Lord’s Prayer in The Large Catechism and articulates how the illustrations reveal Luther’s theology as it developed over time (1). In fact, McNair actually gives little page-space to illustrations and much more to theology. For example, as of 1519, Luther still associated the petition to “give us this day our daily bread” with the Eucharist, and Christ Himself being the bread. However, by 1529 after he published the Greater and Lesser Catechisms (and also translating the Bible into German), Luther had exegeted the prayer as Protestants normally do today, with the phrase referring to normal, physical bread—and therefore, as a supplication for sustenance of the physical body (7-8).

Unlike the consistent use of Old Testament narrative scenes for the Ten Commandment images, the subject matter selected for the Lord’s Prayer is a bit more haphazard. The first topic, “hallowed be Thy name,” shows an apparently 16th-century preacher giving a message to his congregation (3); however, the rest of the pictures are New Testament narrative scenes (the Canaanite woman, the feeding of the five thousand, etc.—although the figures within these scenes are also anachronistic in their attire). In the depiction of the parable of the unmerciful servant, Cranach also utilizes a “continuous narrative” format, where a figure appears multiple times in the single image to indicate time passing and subsequent points in the storyline (9). No other images from the Lord’s Prayer series incorporates this approach.

These woodcuts were not originally created as illustrations for Luther’s catechisms; rather, they were intended as poster-prints known as “broadsheets” (van den Belt 202). Van den Belt states these posters likely had been used to teach children textual information that would have been printed next to the images, namely, “the Ten Commandments, the Twelve Articles of the Christian Faith, and the Lord’s Prayer” (202). Although none of the broadsheets has survived, there is literary evidence that all the illustrations were collected into one poster, which might have been called a “catechetical tablet” (202). However, once the illustrations were included in the early catechisms, subsequent iterations continued to reuse the same imagery, with little or no changes…even when later catechetical passages did not entirely coincide with the portrayals (202-203).

Other instances of Cranach’s pedagogical woodcuts show how the artist appropriated Catholic imagery into the sphere of Protestantism. An indulgence scene of the Holy Family became a “declaration of Lutheran education” that emphasized the Lutheran values of laity literacy and having the Bible available in the common language—"Families were responsible for teaching children to read and study the Bible” (Noble 170, 172-173).

Fig. 14 | Lucas Cranach the Elder, Illustration of the Ten Commandments, 1529 | Image from "The Law Illuminated: Biblical Illustrations of the Commandments in Lutheran Catechisms" by Henk van den Belt, p. 209 | Public Domain

A Possible Solution: Research Reified

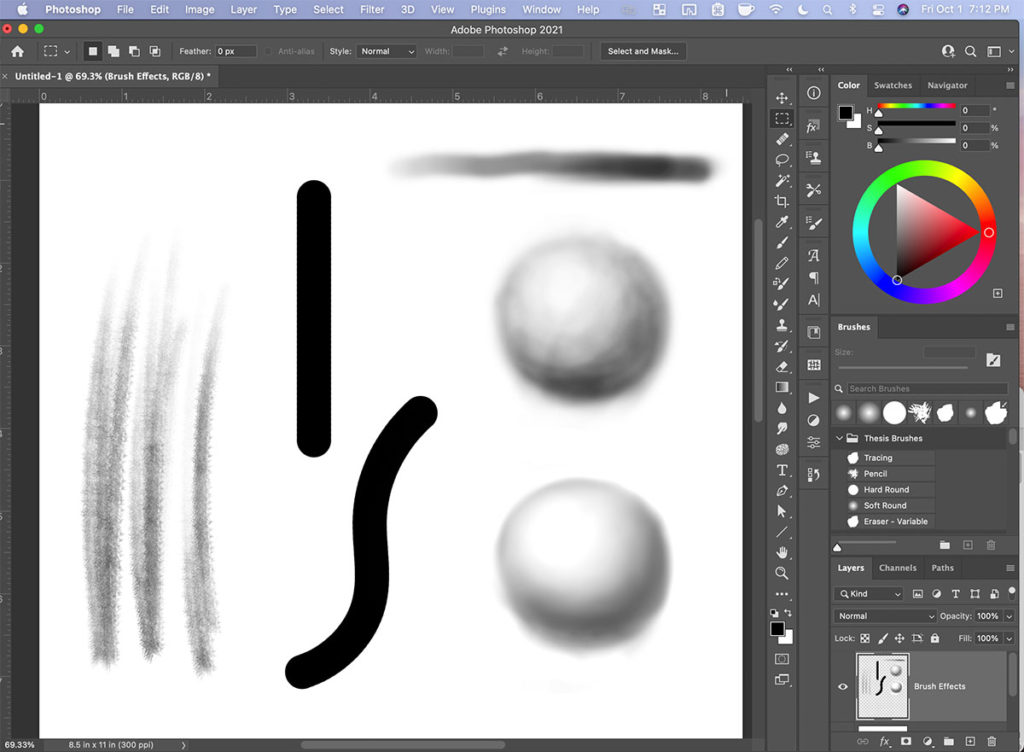

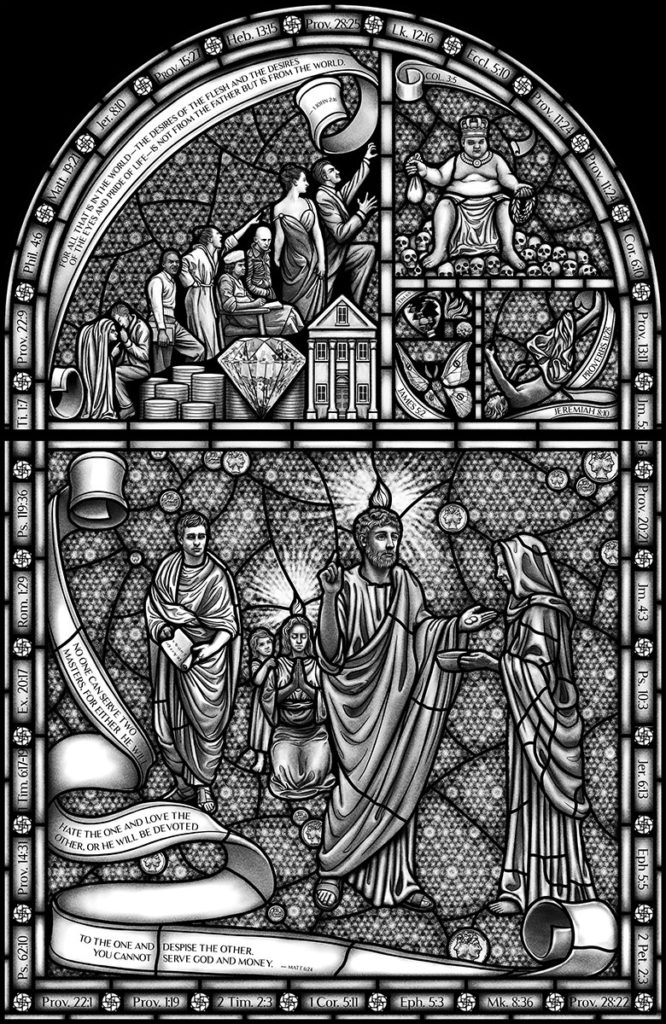

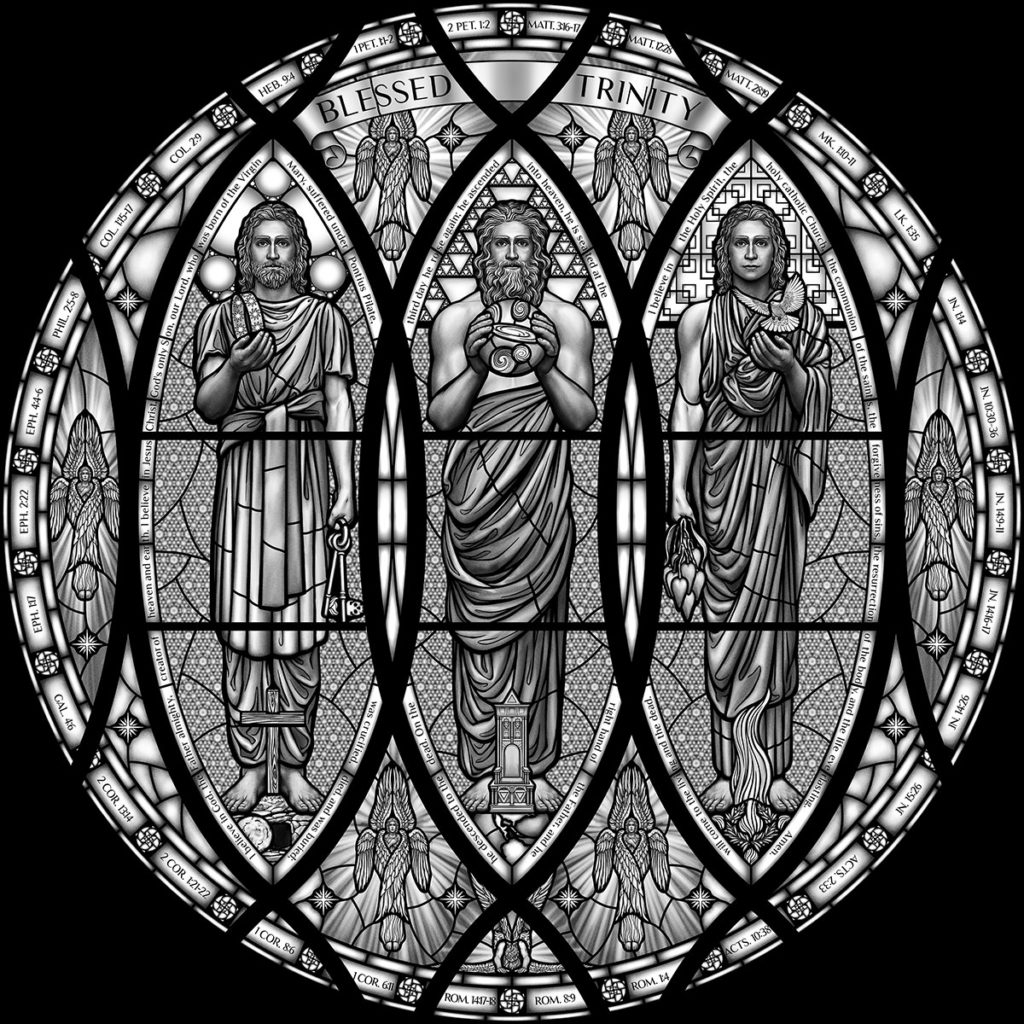

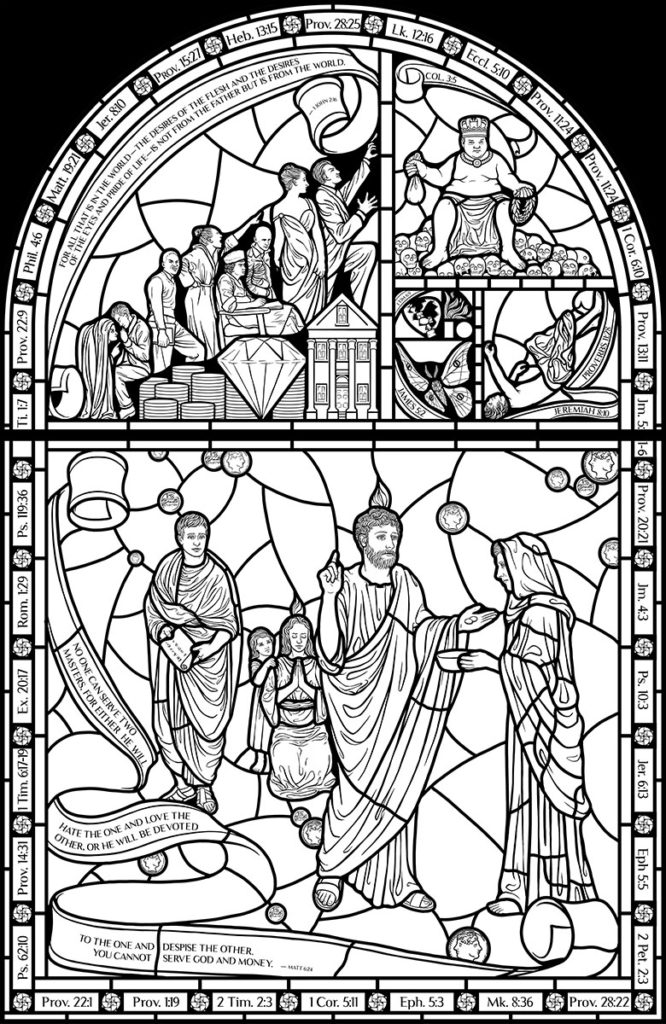

FINAL ARTWORK

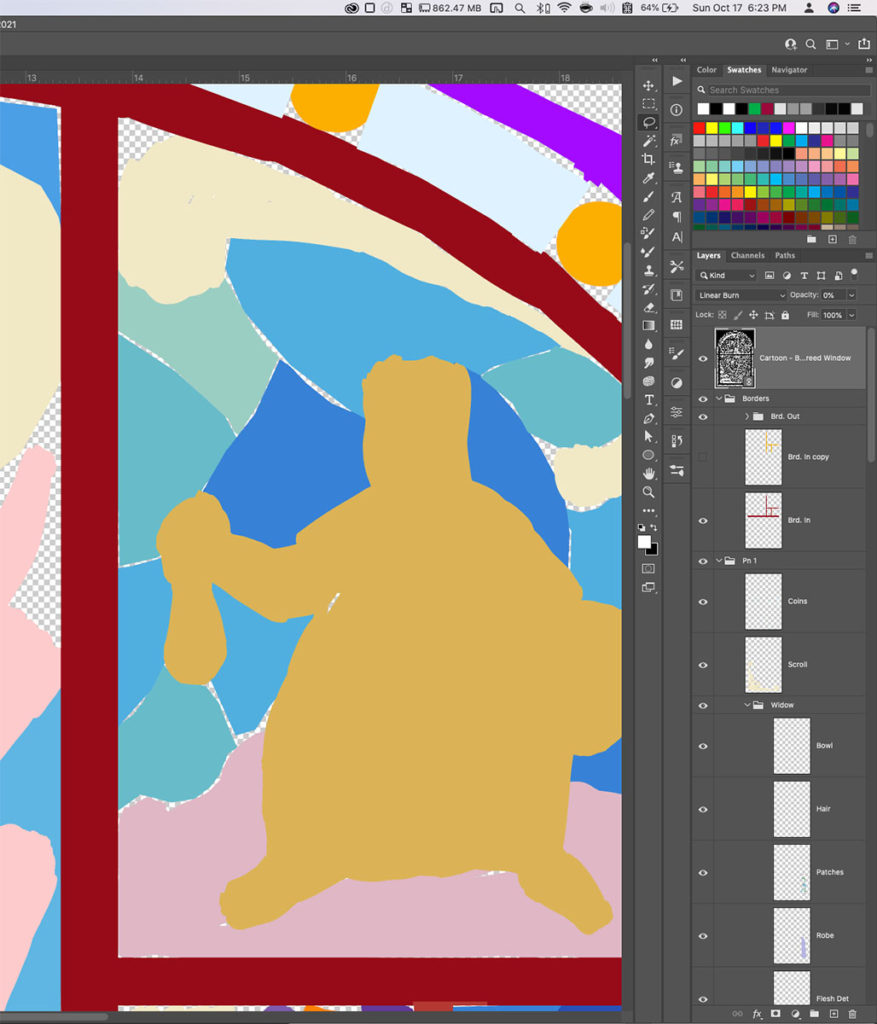

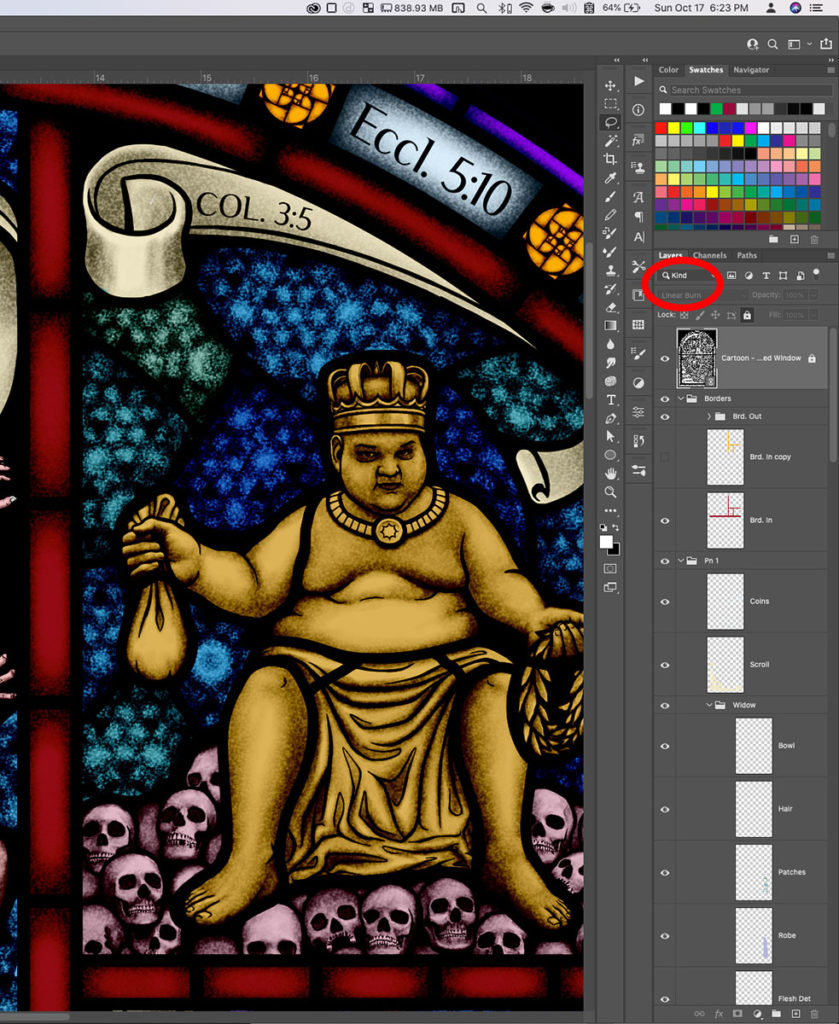

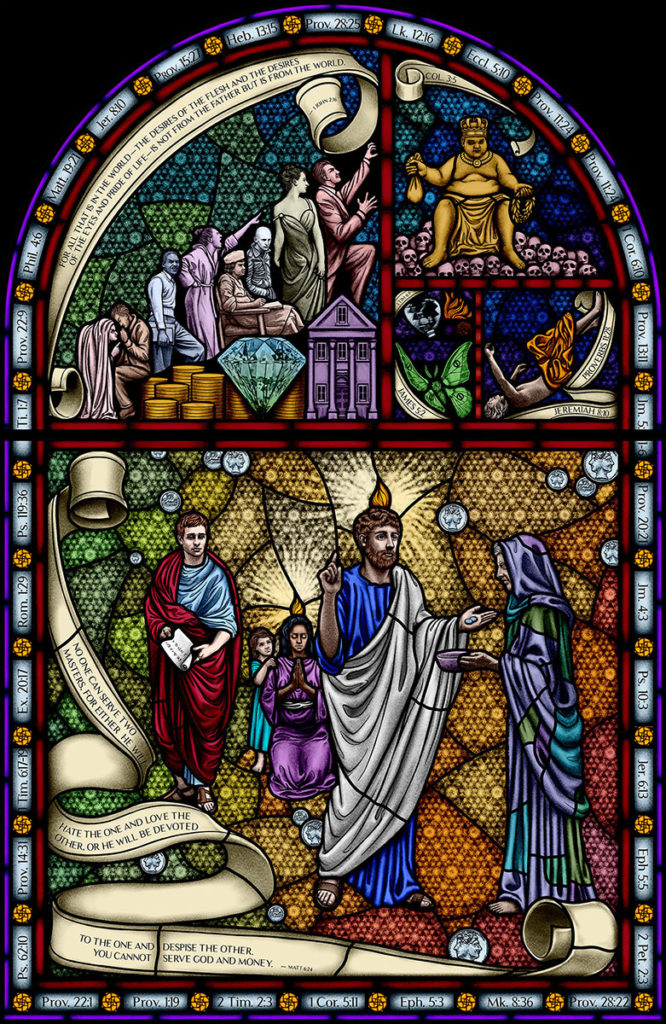

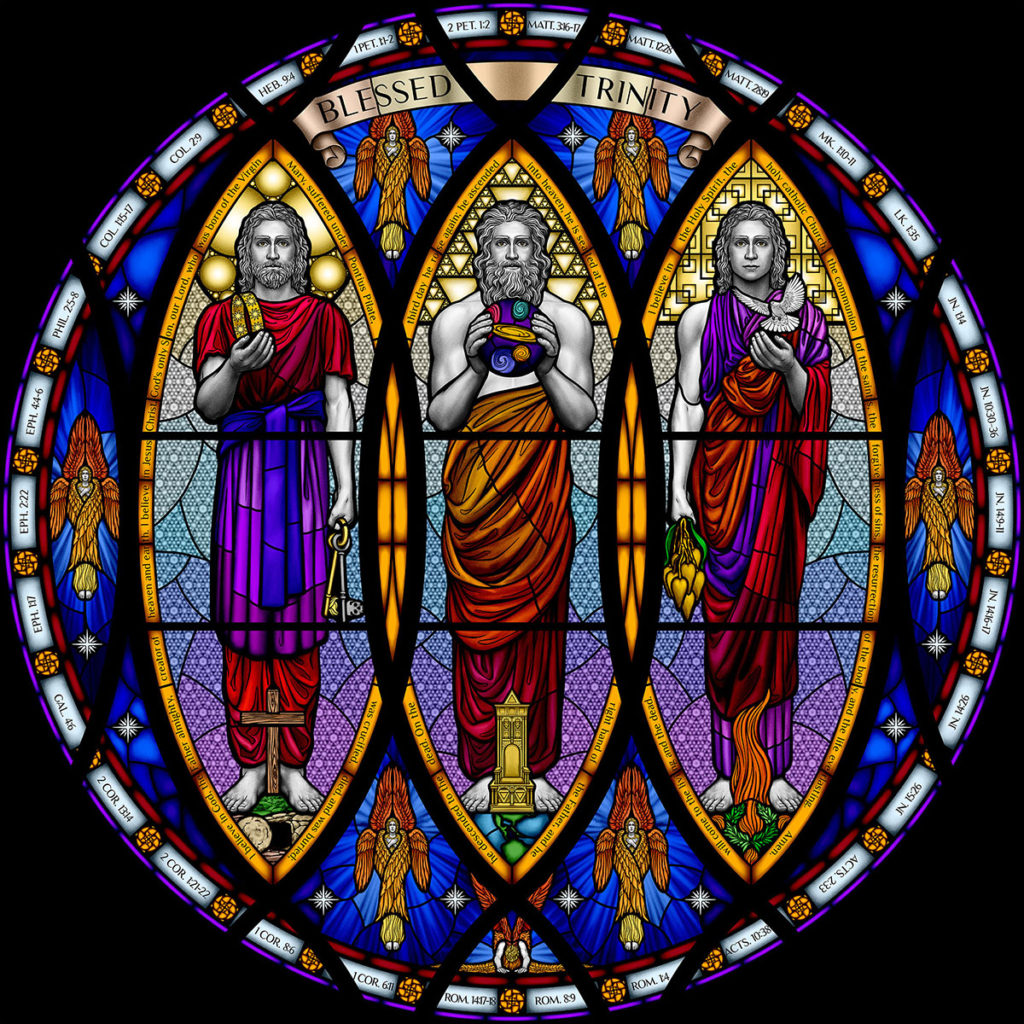

A Fenestrated Forward

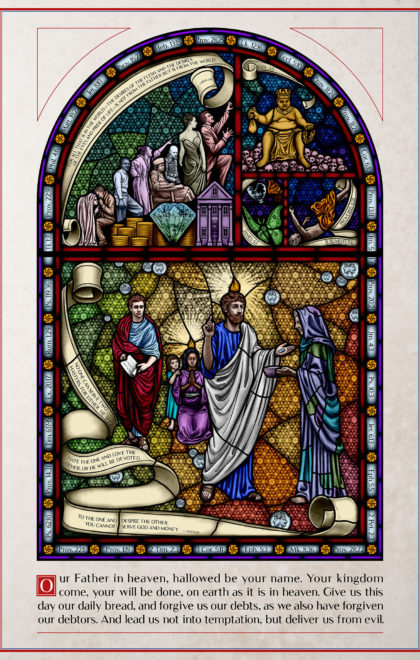

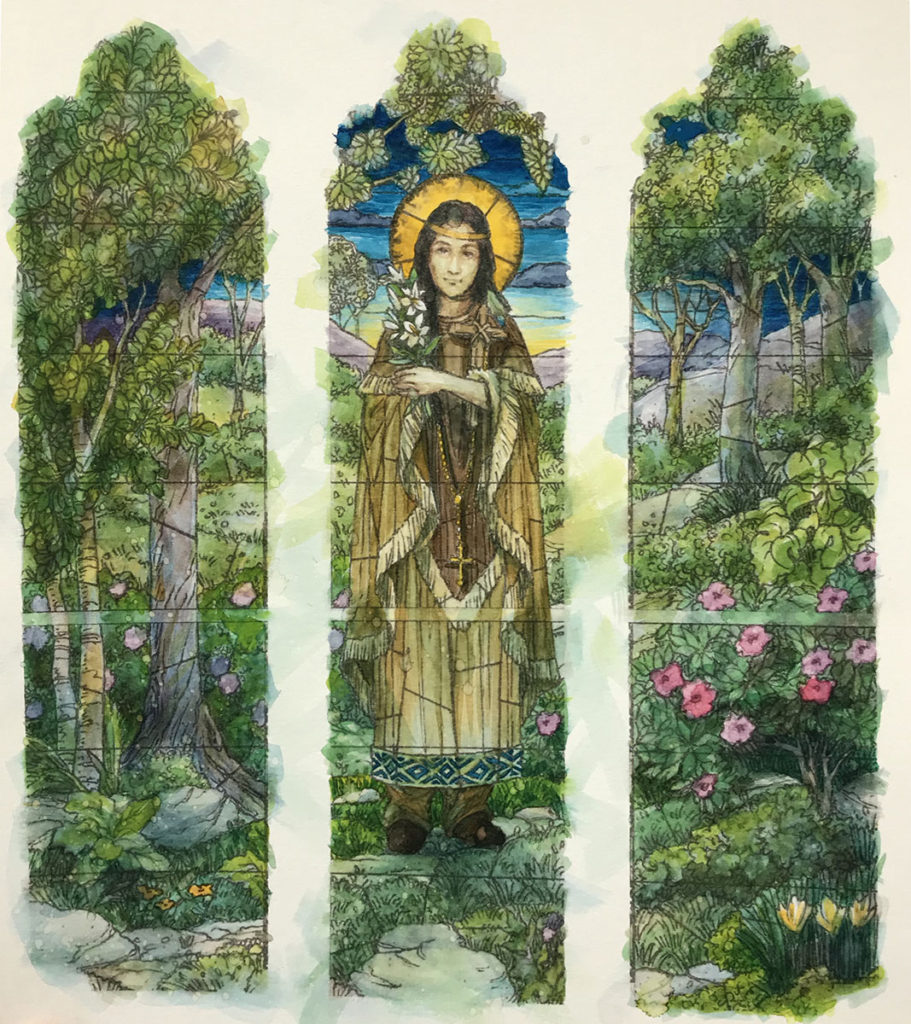

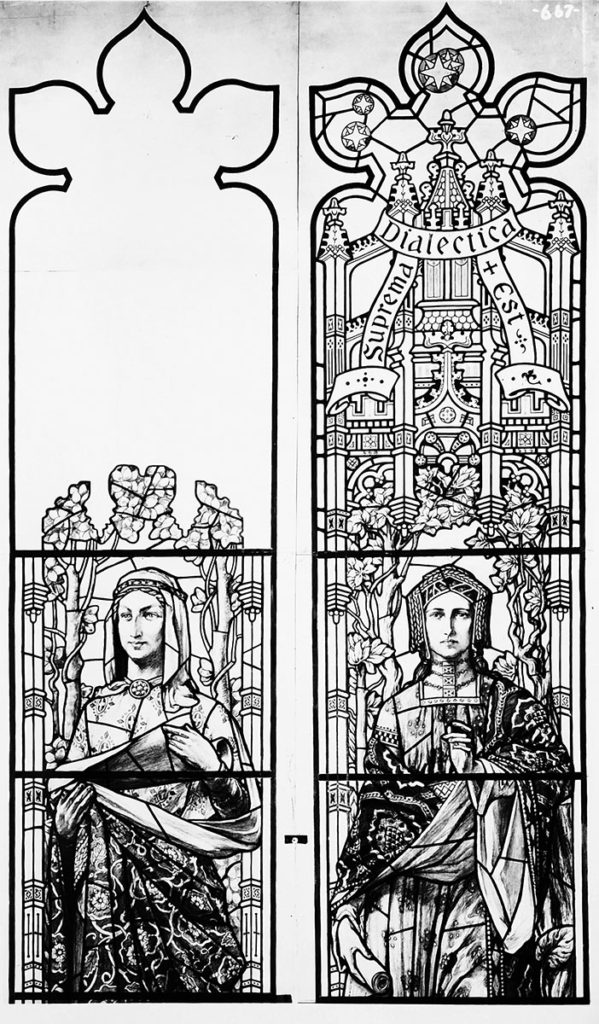

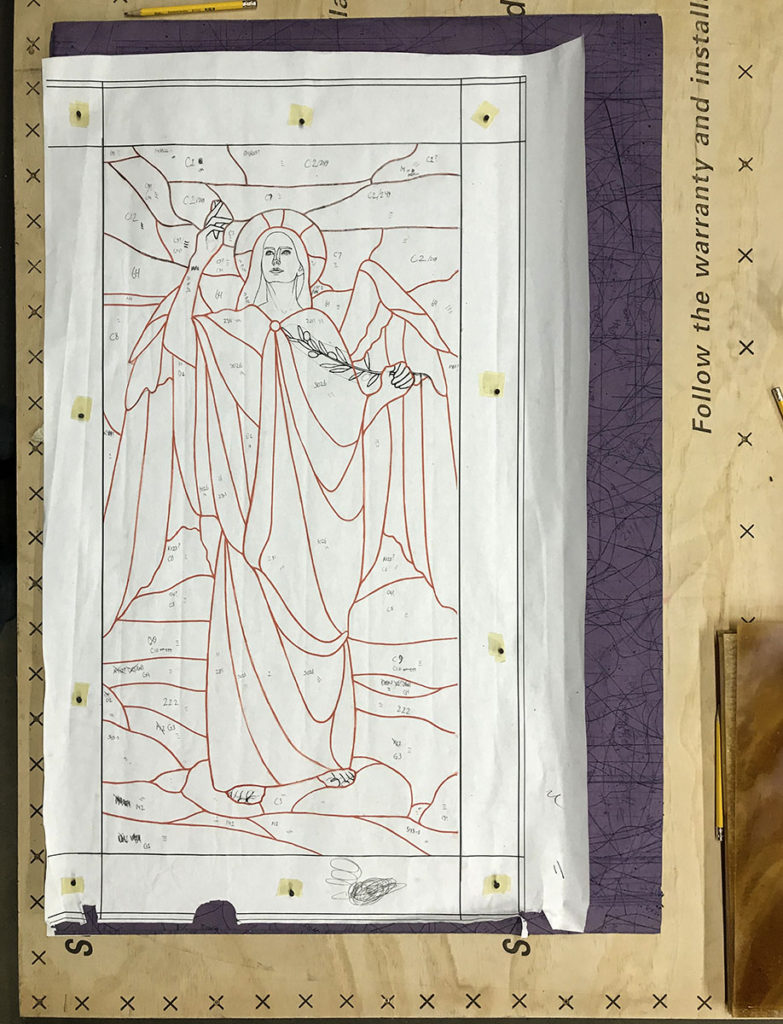

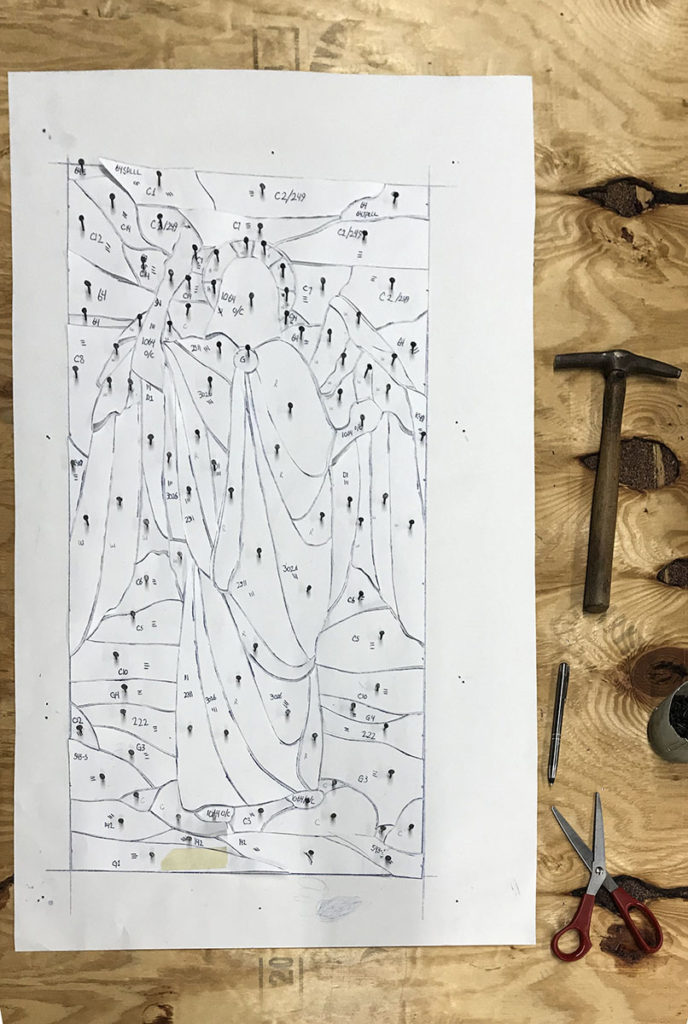

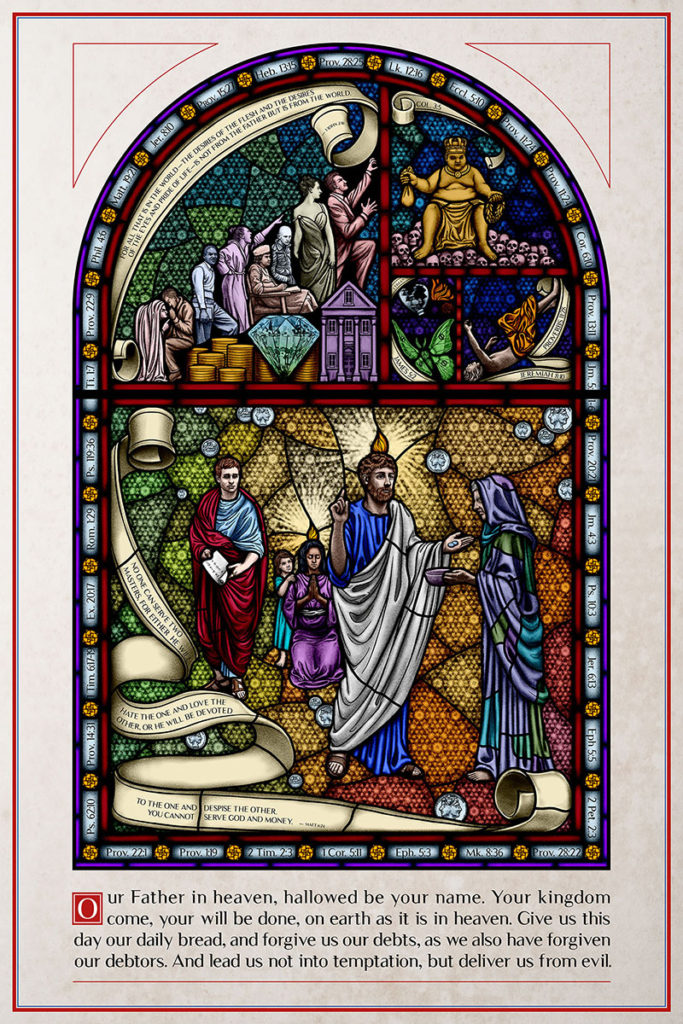

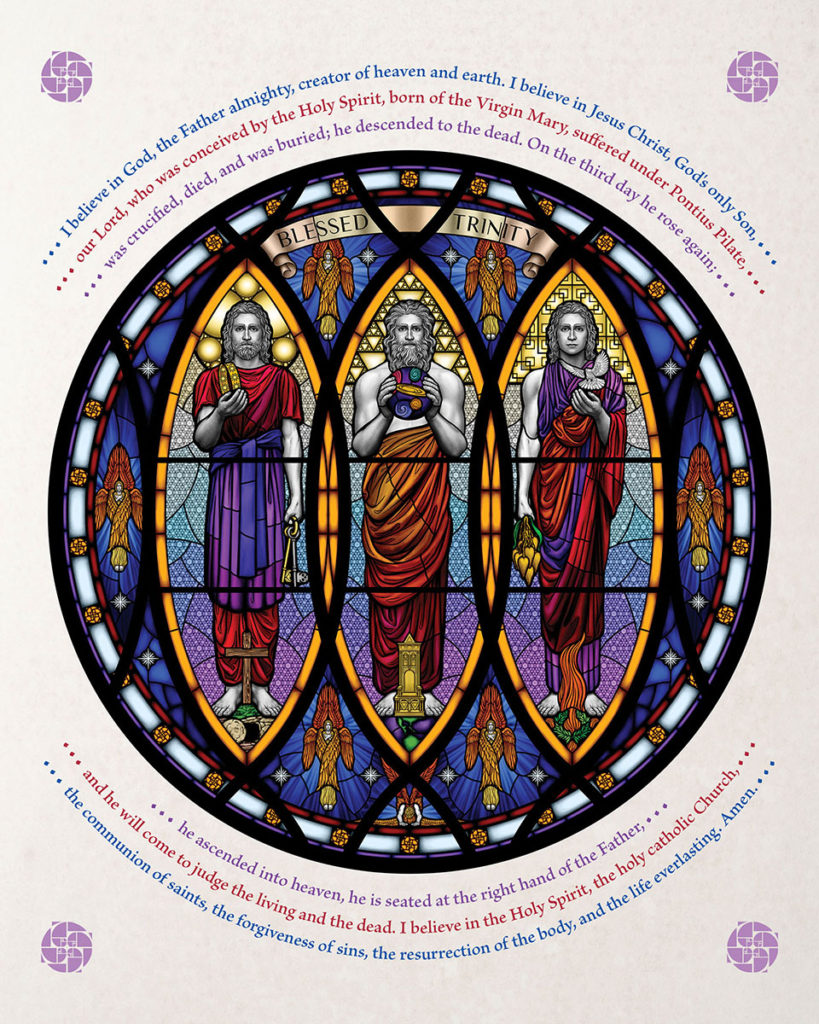

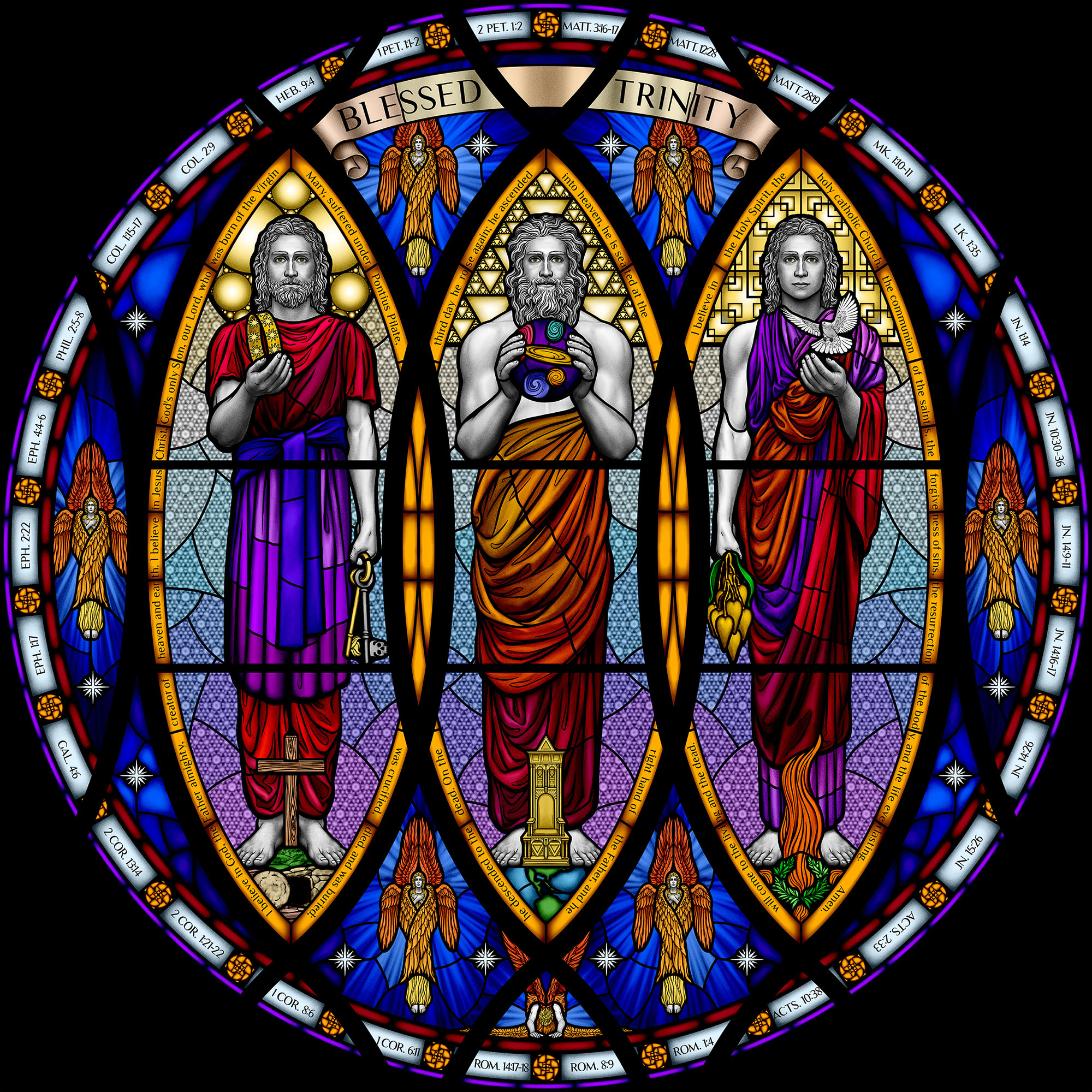

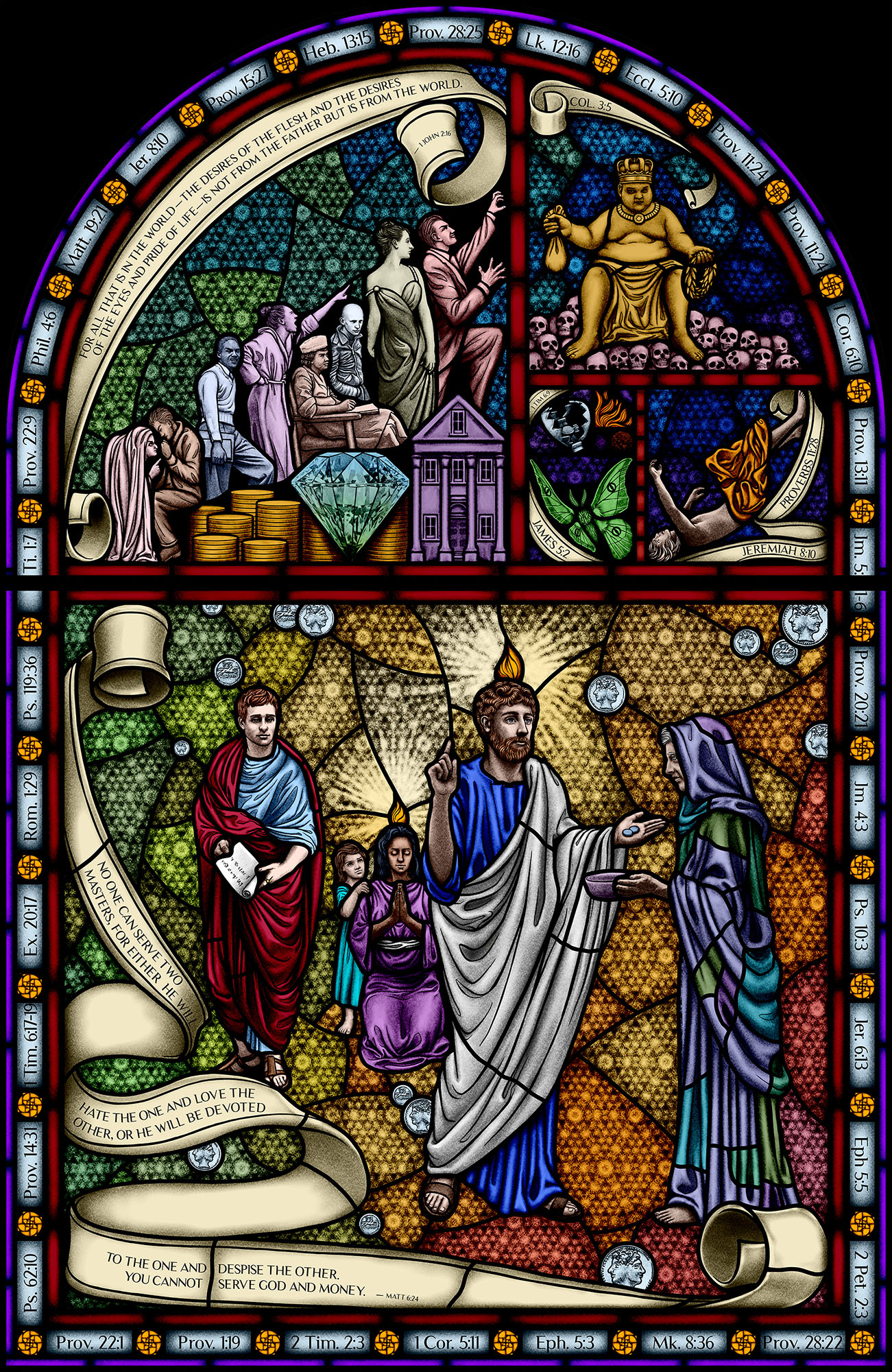

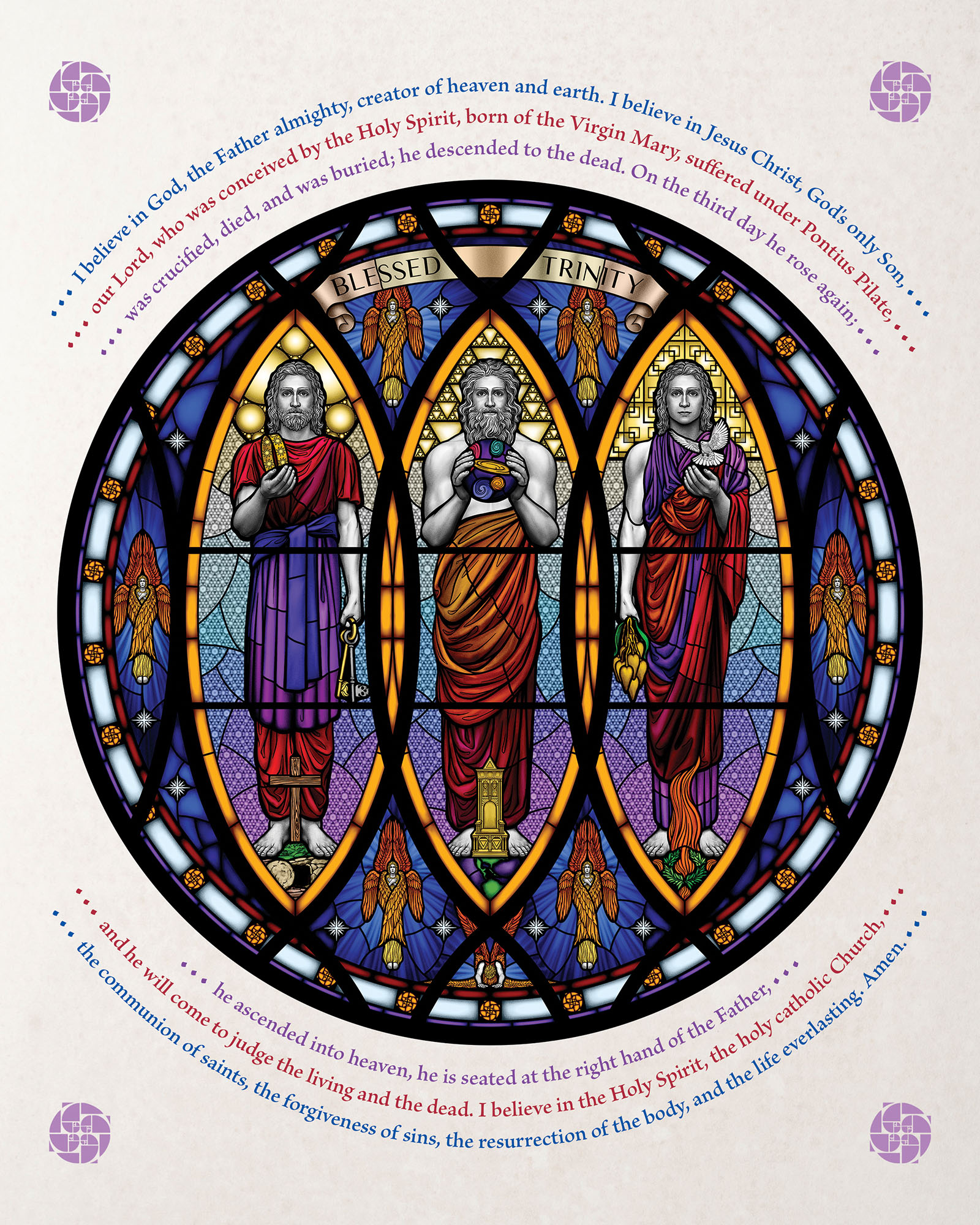

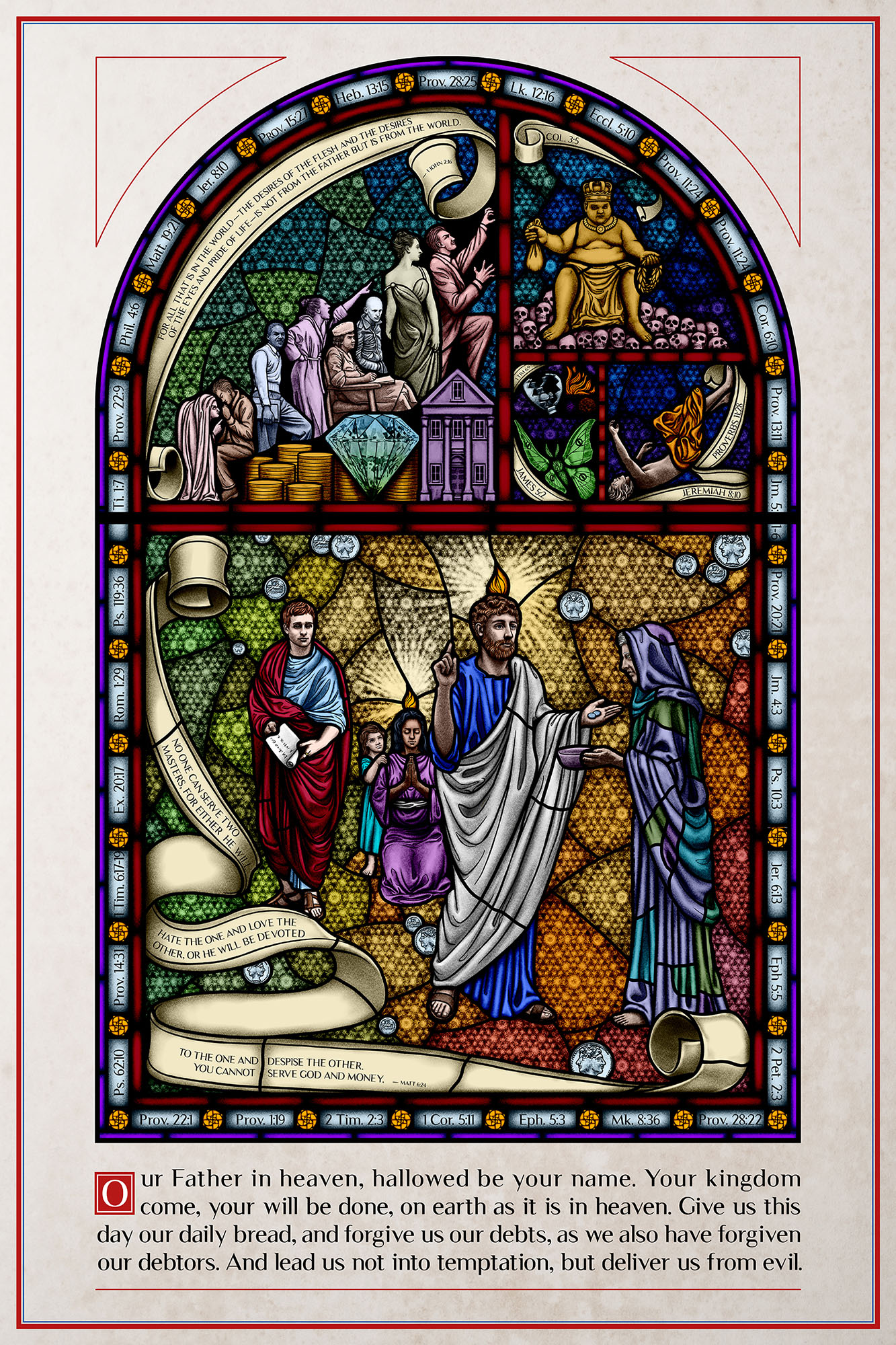

Several assessments had to be navigated as I developed artwork that would aid modern catechesis; this was the pivotal moment when my scholarship informed my artistry. From lesser to greater, these were the judgements at which I arrived: first, the artwork ought to be established within the convention of historical Protestant visual culture while simultaneously not rejecting those worthy elements from both Roman Catholic and more ancient Church traditions. Second, these pictures are intended to encourage contemporary U.S. Protestant viewers of a broad age-range to engage with them seriously both privately and communally. Last, and foremost, these images should equally teach doctrine clearly and exhibit aesthetic beauty.

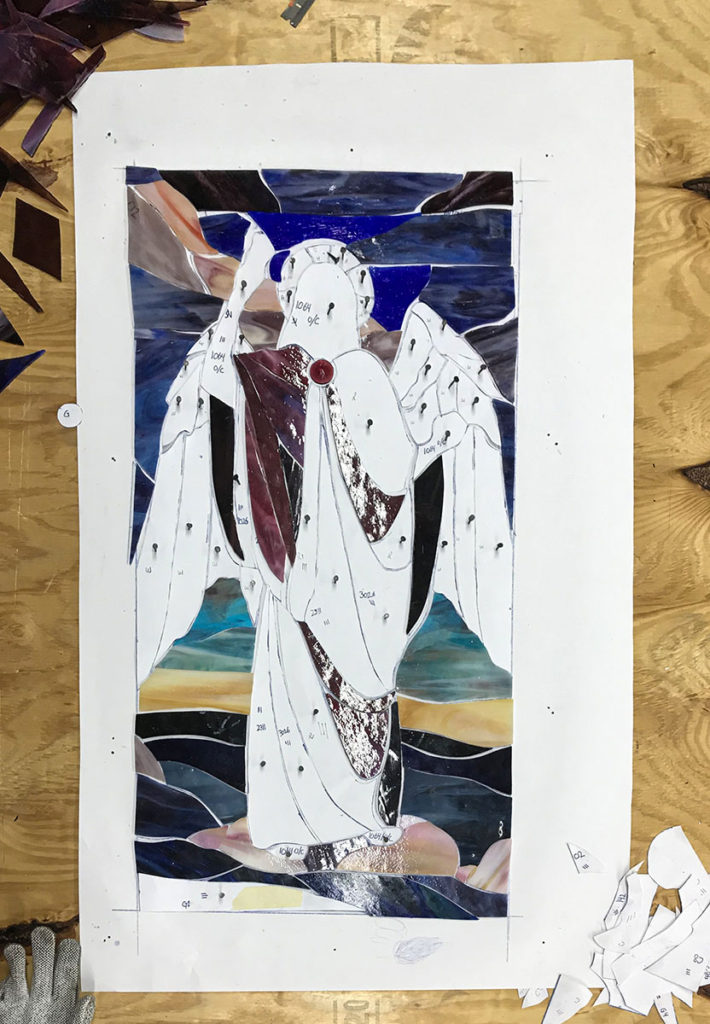

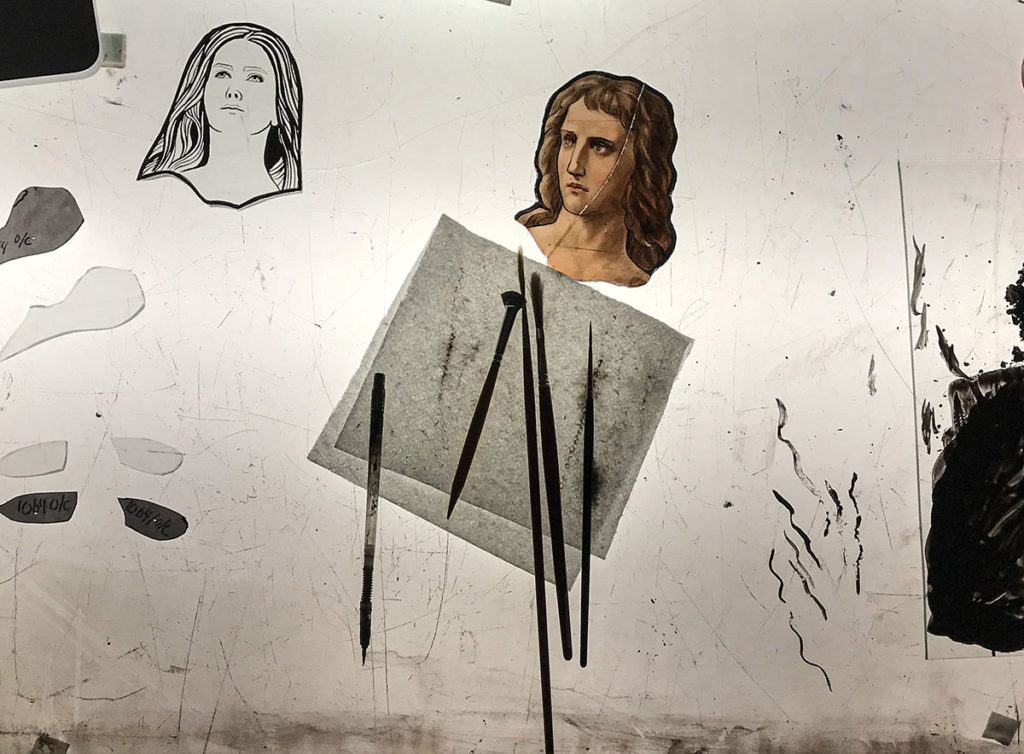

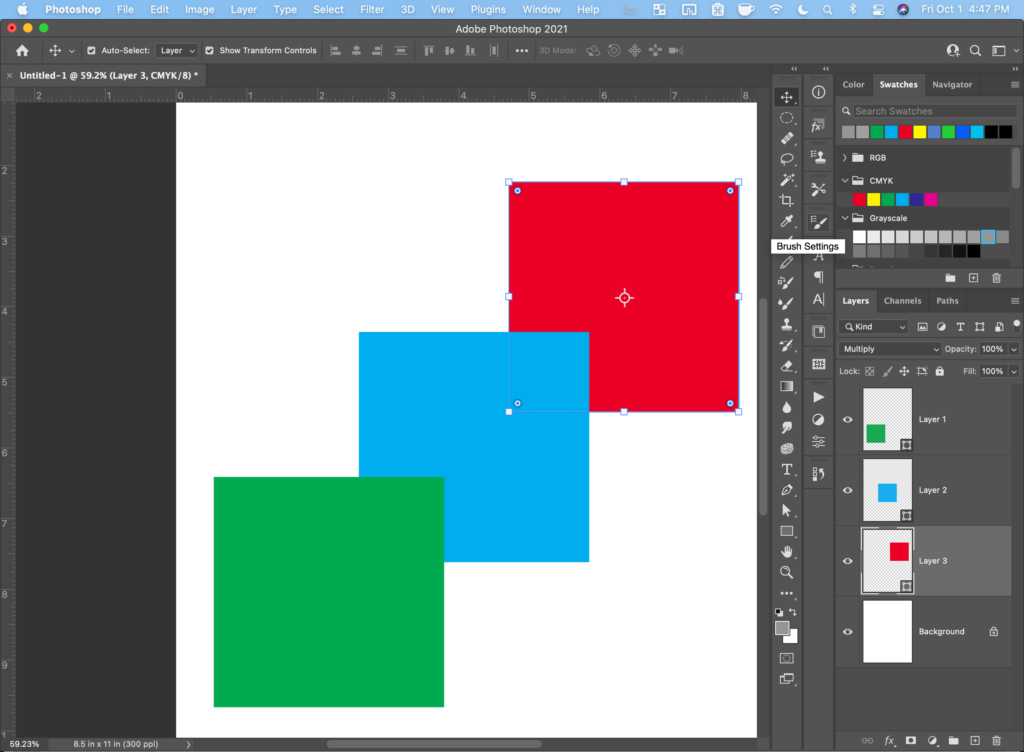

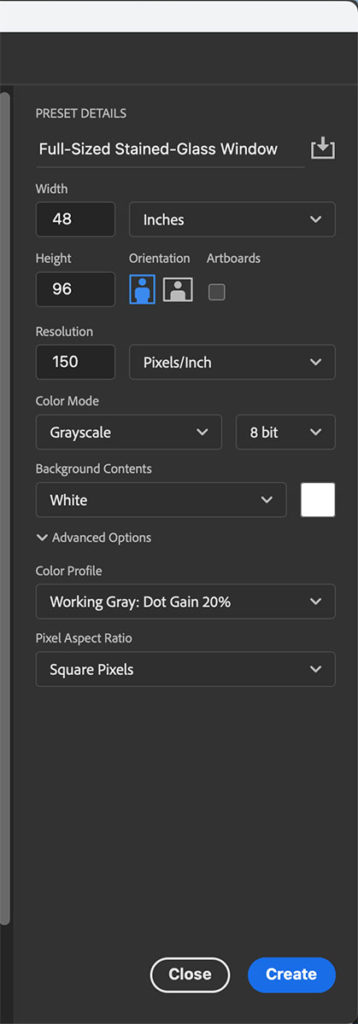

It warrants restating that successful illustrations for renewed catechesis could be accomplished in any number of media; the three objectives listed comprise the core aspects of artwork in this vein and are not dependent on choice of medium. However, beyond stained glass being arguably the quintessentially “Christian” visual artform (Raguin, Style, “Revivals” 316; Lee, et al. 12), other factors also reinforced the decision to work with a primary focus on this unique medium for my thesis; factors which fulfil all three introductory criteria. First, for those Protestants who persist in leaning towards iconoclasm, stained glass was evidently a slightly more tolerated artform during the Reformation, being permitted in churches even by Zwingli, one of the most stridently aniconic Reformers (Michalski 56, 59; Jensen, “Arts” 361). The medium’s brilliant colors and unique reliance on strong transmitted light create a dynamic effect capable of captivating all viewers while intrinsically invoking ancient philosophical and religious symbolism, especially in Christianity, where Jesus Christ is the True Light and the Light of the World (Lee, et al. 6; Ball 243-245; Jn. 1.9, 8.12, 9.39), and where the Church and individual believers are called likewise to shine as lights in the world (Matt. 5.14, Phil. 2.15). Next, stained glass’ inherent, and often literal, connection to church buildings continues the rich tradition of public, communal church art, where uneducated individuals can receive instruction from those more learned in the faith while viewing the pictures (Chazelle 141; Morgan, Forge 50-54; Raguin, Style; Jensen, “Arts” 362; Ball 245, 170-171, 233). In this third sense, Raguin’s remarks concerning religious art “in which the forms of the past promised the renewal of the virtues associated with that past” (“Revivals” 310) could plausibly apply today: the historical gravitas (and perhaps also, for many Protestants accustomed to “black box” churches, the novelty) of stained glass might carry with it an impetus to respect—or at least become more conscious of—the ancient-but-never-old orthodoxy contained in the imagery. Last, these designs do not necessarily have to be singular instances, located in only one establishment. In the history of the craft, precedents abound for reusing compositions or design elements (Raguin Style; Cheney 30). Technology can aid this process in modern times, as a window’s core components (cartoons, cut lines, and so on) can simply be reprinted and a new iteration constructed.

Engaging Aesthetics

For many students of aesthetics through the ages, secular and religious alike, the presence of beauty has been paramount to true works of art; beauty is also demonstrably important to the Triune God, encompassing a facet of the Divine nature (Scruton ix, 1-5, ch. 5; Ryken; Jensen, “Arts” 362-364; Morgan, Forge 197, 217-219). The Bible contains a litany of passages concerning beauty as it relates to God, natural creation, and the artwork of humankind (Ps. 27.4, 50.2, Is. 33.17, Rom. 1.19-20, Ex. 31.2-9, 35.22-35, 2 Chron 2.13-14, et cetera). Writings revolving around the definition of beauty fill libraries; unfortunately, authors often have conflicting positions, especially in modern and postmodern cultural milieus. Therefore, the works of art for this thesis take a two-pronged approach to achieving objective beauty: a redemptive presentation combined with technical excellence (Ryken; Schaeffer 82-83; Jensen, “Arts” 365; Scruton ch. 5, ch. 8).

Redemptive Presentation